This blog entry is an adaptation of Dr. Hoffman’s essay, “No Wake for Ares,” Naval Institute Proceedings, December 2015. It is posted here with the permission of and gratitude towards the U.S. Naval Institute.

The tides of war are not receding. The Harvard psychiatrist Steven Pinker, in his bestselling book The Better Angels of our Nature offers a detailed explanation of mankind’s evolution from a Hobbesian world of brutish, short and violent lives to today’s benign environment. Pinker offers a multidisciplinary approach with a swirl of statistics.

It’s a popular book despite some counter-arguments on causation and Euro-centrism. Several authors have embraced Pinker’s research to extol policy implications about strategy and security resources, without absorbing his caveats against predicting the future. For example, one author quipped that “war as we know it, long thought to be an inevitable part of the human condition, has disappeared.” According to others, “we live in a remarkably safe and secure place, a world with fewer violent conflicts and greater political freedom than at virtually any other point in human history.”

There are grains of truth in the upbeat assessments of some of these analysts. Human violence was in significant decline for many years, and especially so in the developed world. The end of the Cold War ushered in a remarkably rare period of peace, with a sharp drop in the number of wars and reductions in the duration and costs of wars. That said, the last 25 years are quite a unique era, and U.S. security and the risks we have to manage are not measured by aggregated global statistics. Moreover, as this posting argues, the prognostications above fail to account for possible changes in the emerging security environment. Pinker was clear on this point, the substantial progress to date is not irreversible.

In fact, the recent decline in major conflict frequency and overall reduction in battle deaths, is a positive reflection of what we and our Allies have been doing for a generation in terms of working to sustain a rules-based international order. If true, the use of Pinker’s argument as evidence to embrace retrenchment and reduce U.S. defense spending is perversely counter-productive. A less robust military component of U.S. strategy would be less engaged, increasingly less forward deployed, and offer less deterrence to would be aggressors.

We need to develop a prudent sense of awareness of the geopolitical context that could evolve from a plausible projection of drivers in the near future, and the potentially grave consequences that may emerge. Contrary to untested assumptions about linearity in past patterns, trends are not immutable and they do not proceed in only one direction.

Contrary to untested assumptions about linearity in past patterns, trends are not immutable and they do not proceed in only one direction.

Conflict Trends: Looking Backwards

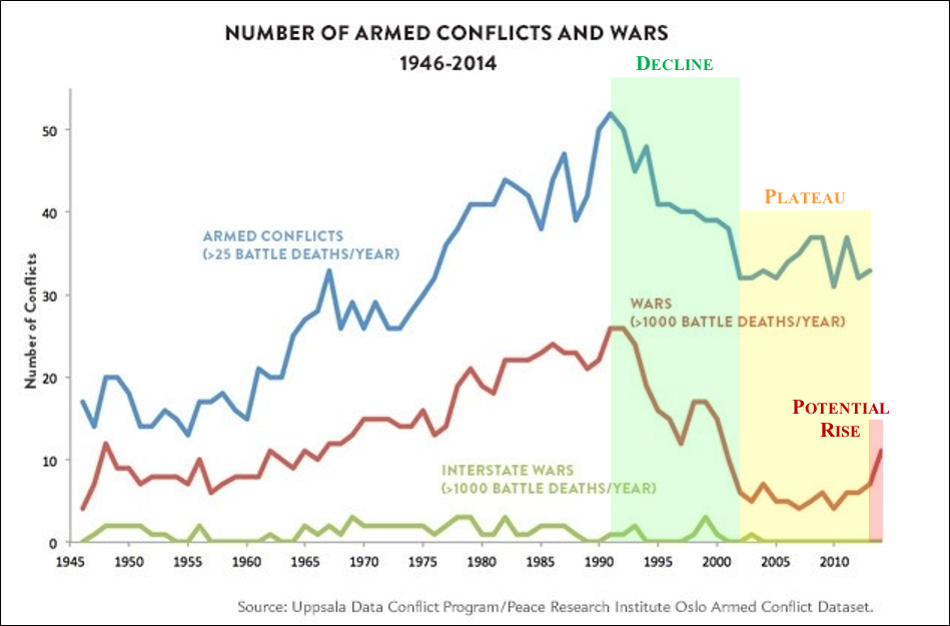

The chart below captures major conflict data from the last half century. The period 1991 to 2003 illustrates a decline in armed conflicts. But this data from the Uppsala conflict data center clearly shows a plateauing of “armed conflicts” (blue line) and the emergence of an increase in “wars” (red line) in the last decade reflecting events in Ukraine, Syria and Iraq. Lethality of conflict, measured in combatant and civilian deaths is also up appreciably.

Figure 1: Armed Conflicts and Wars 1946 to 2014

Thinking Forward

Even more important for policy makers is the simple caution that, just as in any reputable stock prospectus, past performance is not indicative of future performance. What factors or drivers might cause wars to trend along different paths? Certainly, as Pinker and others have noted, globalization and economic interdependence helped dampen the incidence of state on state war. Others however contest the idea of economic determinism, and others argue that globalization has little causal relationship to wars or conflict.

But what dark forces might appreciably bend what some see as an ineluctable and linear pattern? In this section we offer several possible other drivers:

American Engagement. A dominant factor in preserving order and stability over the last 20 odd years has been the unipolar character of the international system. The dominant position of the United States, especially in economic and military power, is the last generation’s most significant geopolitical characteristic. Some scholars suggest that American retrenchment would be a positive strategic move today. But the U.S. intelligence community forecasts that a declining U.S. willingness to engage and lead, or a “slipping capacity to serve as a global security provider would be a key factor contributing to instability.”

This is not an argument for a perpetual Unipolar era or even American primacy, but it is a warning about a possible change in a key variable in tomorrow’s security environment.

Geo-political Competition. Pinker’s factors overlook the major driver that most security studies scholars use to explain conflict between states. The prevailing post-Cold War power structure, the so-called unipolar moment, contributed much to subdued levels of interstate conflict and war over the past generation. Alterations to the current power system by China’s significant economic development and its rapid military modernization could conceivably produce a great power competition that erupts into a war. As in the case of Norman Angell’s flawed assessment a century ago, we need to factor in human agency and the potential for miscalculation. In the emerging multipolar system, with different players in different dimensions (political, military, socio-cultural, and economic) and less relative power difference between states, we will likely see a greater propensity for regional challengers to attempt to resolve outstanding political grievances. As noted by another scholar, “Historically, transition periods marked by hegemonic decline and the simultaneous emergence of new great powers have been unstable and prone to war.” According to Harvard’s Graham Allison, in 12 out of 16 cases the emergence of rising powers produced conflict with the existing predominant powers. The tragedy of great power conflict can still be avoided, but not by ignoring the problem.

“Historically, transition periods marked by hegemonic decline and the simultaneous emergence of new great powers have been unstable and prone to war.”

Declining Alliance Capacity. Following from the previous driver the role of alliances must be understood. America’s allies and partners have been material contributors to the sustained security challenge posed by the Cold War. They have been equally material to security in Iraq and Afghanistan over the last decade. Unfortunately, many of America’s traditional allies face social, demographic and economic challenges. Europe, in particular, could produce a suite of partners who are older and smaller demographically, and much poorer in both economic clout and in military spending. While the European Union economies have recovered from the fiscal crisis of 2008, their collective defense spending is roughly 15 percent lower than 2007 in constant dollars despite Mr. Putin’s aggressive acts.

Japan faces many of the same challenges with an aging population and a severe debt-to-GDP ratio that makes increases in security spending most unlikely. Weak and uncertain alliance structures contributed to disaster in 1914, and we face the same problem today and for the near future. Weak alliance networks and reductions in military preparedness, Sir Lawrence Freedom has persuasively argued, can weaken deterrence and increase the risks of major power conflict. For that reason, this factor could increase the possibility of interstate war and its duration.

Technological Miscalculation. The evolving character of technology will have a commensurate impact on our security, sometimes in ways we have not yet imagined. Technology is not the sole driver of change in military revolutions, but our age is replete with potentially disruptive sources of innovation that will change how societies fight. Many of the new emerging technologies like quantum computing, 3-D printing, robotics, directed energy, and nano-technology will have military applications, and could prove to be game changers to the country that first successfully employs them. Cyber security will be a continual challenge, even if as Thomas Rid argues it does not technically qualify as a form of warfare, as it can be used to enable or disable crucial elements of our national security and economic system. Crisis instability appears to be growing, given the uncertain balance of capability between nations and the uncertain character of cross-domain technologies. One must ask if the reliance of states on space or cyber connectivity is increasing the need for preemptive actions, which increases crisis instability.

Resource Tensions. Resource pressures are often cited as a source of conflict, especially energy. China continues to act assertively in the South China Sea, presumably in the belief that either hydrocarbons or other scarce resources can be found there. No doubt Russia still hopes to weaponize its substantial energy resources to coerce European governments to bend to its will. Yet, due to the decline in demand for fossil fuels, and increased sources in North America and elsewhere, a demand for fuel is not likely to stimulate war. Energy will remain entangled in our security concerns but is unlikely to be a driver. Instead of energy competition, the future will be marked by greater interest in environmental challenges that impact food security. Food security in Asia will continue to grow as a challenge, due to rising population requirements, and degraded sources of water. Other ongoing conflicts, like Syria for example, happened in ravaged agricultural regions with food price spikes and drought as stressors. An increased likelihood of instability from the nexus of environmental damage, water pressure and unstable food prices drive up the probability of intra-state conflict.

Violent Extremism. Political violence directed against noncombatants to provoke shock and terror is on the rise, and has been for some time. Groups like Al Qaeda, ISIS and Boko Haram are filling security vacuums and exploiting political dissatisfaction throughout the Middle East and North Africa. The frequency and lethality of acts of terrorism appear to be escalating as these groups compete with regional factions and each other for media attention, funding, and recruits. As extremist groups embrace emerging technologies, the potential for disruption and violence may increase further. Though not an existential threat by any means, violent extremist organizations can incite wars on their own, and extremist violence is shifting regional power balances, spreading insecurity, and aggravating ethnic and religious animosities, all of which can spiral into new wars.

Peacekeeping Fatigue. A large increase in UN peacekeeping operations has correlated with a decline in the number of active conflicts. However, the continued success of UN and regional PKO is predicated upon continued international support, the availability of countries able and willing to provide troops, and resources to support them. All three requirements could be weakened in the future. International support requires a consensus of major players on the Security Council, which may evaporate in the middle of increased competitions between the West and China or Russia. The availability of troops could decline if major states are unwilling to pay for the operations or if smaller states face higher security dilemmas at home, and cannot sustain external PKO. If so, it’s probable that such operations will be fewer, less capable, and hard pressed to preserve the peace. That would be a shame given that they are a good strategic investment.

All told, the combined impact of these trends could generate a return to more significant levels of conflict and increased levels of casualties and other costs. Without any doubt, there was a pattern of declining violence since the end of the Cold War. However, this cycle is not unique to human history and could be reversed, if we let complacency set in. Already, levels of conflict are again increasing and that a more contested era of geopolitics is gathering. We should continue to be prepared to deter aggression, work collectively to build a better peace, and preserve order. The one thing we should not do is delude ourselves that we have escaped History or geo-politics. The storm tides of war can surge back.

[Photo by Robert Scarola]

An excellent analysis & I agree to most points Dr Frank makes.