On September 17, 1862, Federal cavalry captured the ford at Shepherdstown, cutting off the retreat of the Confederate Army at Antietam. Maj. Gen. George Brinton McClellan declared an end to the rebellion after the overwhelming Union victory and Gen. Robert E. Lee’s unconditional surrender—vindicating himself after having previously been removed from command of the Army of the Potomac and cementing his legacy as one of American military history’s greatest fighting generals.

Or so it could have been. Instead, the reality of what transpired at Antietam would have long-lasting effects on the course of the Civil War and holds lessons on the consequences of failing to implement the tenets of Mission Command on the battlefield.

McClellan believed that divine providence had placed the instrument in his hands to defeat Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia and end the war. A copy of Special Orders No. 191, wrapped in three cigars and dropped by a negligent Confederate courier, was discovered by a corporal of the 27th Indiana Volunteer Infantry Regiment in a field outside Frederick, Maryland. The orders included details of Robert E. Lee’s entire campaign plan. Most importantly, it gave the intelligence that Lee would divide his army, having part of the corps of Maj. Gen. Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson attacking the Federal garrison at Harpers Ferry. All McClellan had to do was act quickly, march his army to that place, defeat the outnumbered rebels, save the garrison, and then attack the other part of the Southern army, defeating them in detail. McClellan was elated with the discovery. He exclaimed, “Here is a paper with which, if I cannot whip Bobbie Lee, I will be willing to go home.” His words would be prophetic.

McClellan had recently been reinstated in command of the Army of the Potomac. He had led the disastrous Peninsula campaign earlier in the year, which exposed his severe limitations for high command. McClellan’s meteoric rise in rank was very typical of the professionally trained regular army officer of the day. In 1857, he was a successful captain in 1st US Cavalry, with an admirable record in the Mexican-American War as an engineer officer on Maj. Gen. Winfield Scott’s staff. He was possessing of an intellectual capacity for professional contributions, publishing treatises and designing a cavalry saddle still in use as late as 1943. He jumped from captain to brigadier general with the beginning of hostilities, due to astute politicking. He won minor victories in western Virginia, at a time when any success was needed, and which propelled him to fame and advancement.

McClellan had been successful in everything he had done heretofore, and suffered from a hugely inflated ego, encouraged by the Northern press. They saw him standing with his right hand wedged between the buttons of his uniform and christened him the “Young Napoleon.” He did not discourage the resemblance. T. Harry Williams, in Lincoln and His Generals, perfectly exposed his character:

He was a fine organizer and trainer of troops; and his men, sensing that he identified with them, idolized him. In preparing for battle he was confident and energetic, but as he approached the field of operations he became slow and timid. He magnified every obstacle; in particular, the size of the enemy army increased in his mind the closer he got to it. In battle he tended to interpret sights and sounds in his front as unfavorable to him; he hesitated to throw in his whole force at the supreme moment; and he withdrew when bolder men would have attacked.

When gifted with the perfect piece of intelligence with which to destroy Lee, he did nothing for eighteen crucial hours. Moving slowly, as was his habit, he allowed the dangerously exposed garrison at Harpers Ferry to be sacrificed and permitted Lee to concentrate his forces on the ground of his choosing at Sharpsburg. An audacious commander in the mold of Frederick the Great would have seized this opportunity and struck like a thunderbolt. McClellan was not the man for this type of swift, pivotal stroke.

The battle was directed in an uncoordinated fashion. Shortly after dawn on the Federal right, the intense struggle for Miller’s Cornfield consumed men on both sides in a maelstrom of death. Union Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker remembered that “every stalk of corn in the northern and greater part of the field was cut as closely as could have been done with a knife, and the slain lay in rows precisely as they had stood in their ranks a few moments before. It was never my fortune to witness a more bloody, dismal battlefield.” This was not hyperbole. In the late morning, severe and inconclusive fighting in the Union center at the “Bloody Lane” left the dead piled in heaps along a sunken farm track. On the Union left lay the best chance to destroy the rebels. There, at 9:00 AM, Maj. Gen. Ambrose Burnside received an order from McClellan to carry the lower bridge over Antietam Creek, “at least to create a diversion in favor of the main attack, with the hope of something more.” If Burnside had carried out the order expeditiously, it may quite well have been decisive. Through his ineptitude, the bridge was not carried until 1:00 PM, although his eighty-five hundred men greatly outnumbered the five hundred Georgians of Brig. Gen. Robert Toombs’s brigade, posted on high ground perfectly suited for defense. A belated reconnaissance exposed Snavely’s Ford, well downriver. Burnside then took until 3:30 PM to launch his ordered main assault on the Confederate right.

After the capture of the bridge and commanding position, the correct course of action was for Burnside to turn the right flank of the Confederate Army, causing Lee to abandon his positions and fall back toward the Potomac. McClellan then should have ordered the Federal cavalry corps of Brig. Gen. Alfred Pleasonton and attached horse artillery to immediately ride for and capture Boteler’s Ford over the Potomac River at Shepherdstown, which would have effectively trapped Lee’s Army. Why did he not? Many reasons. One is that the Union cavalry were not placed properly nor used effectively at Antietam.

Napoleon said, “Without cavalry, battles are without result.” By doctrine in this period, cavalry was often used to pursue a beaten enemy, turning a retreat into a rout. The Federal cavalry should have been posted on both flanks, prepared for this opportunity. The failure to do so is especially notable when compared with the positioning of the Confederate cavalry. Led by the “bold dragoon” Maj. Gen. J.E.B. Stuart, one brigade (Col. Thomas T. Munford’s) guarded the right flank. On the left, the brigades of Brig. Gen. Fitzhugh Lee and Brig. Gen. Wade Hampton, along with the Stuart Horse Artillery, were placed on the low ridge of Nicodemus Hill. They were in a superior position to affect the fight in Miller’s Cornfield, providing enfilading fire and helping create there what Confederate artillerist Col. S.D. Lee called “artillery hell.” In battle, Stuart was in his element:

[He] seemed to be everywhere among the field pieces and in the cornfield, with the black plume in his hat fluttering in the southeasterly breeze that wafted the smoke of the battle into the woods. He sang to himself, as was his habit, leading his skirmishers against [Union Brig. Gen. Willis] Gorman’s line. Confederate canister and shot whistled over the tops of the cornstalks into the ridges of the West Woods.

Jackson lauded Stuart’s part, saying, “This officer rendered valuable service throughout the day. His bold use of artillery secured for us an important position, which, had the enemy possessed, might have commanded our left.”

This action contrasts sharply with an account from Lt. Charles Francis Adams, Jr. of the 1st Massachusetts Cavalry, as the entire Federal cavalry division (four thousand men) spent most of the day “guarding” the headquarters of the army or in a valley west of Antietam Creek, not engaged. He described the situation as “unmistakenly trying,” but recalled that “the noise [of the shelling] was so deadening; gradually it had on me a lulling effect; and so I dropped quietly asleep—asleep in the height of the battle and between the contending armies!”

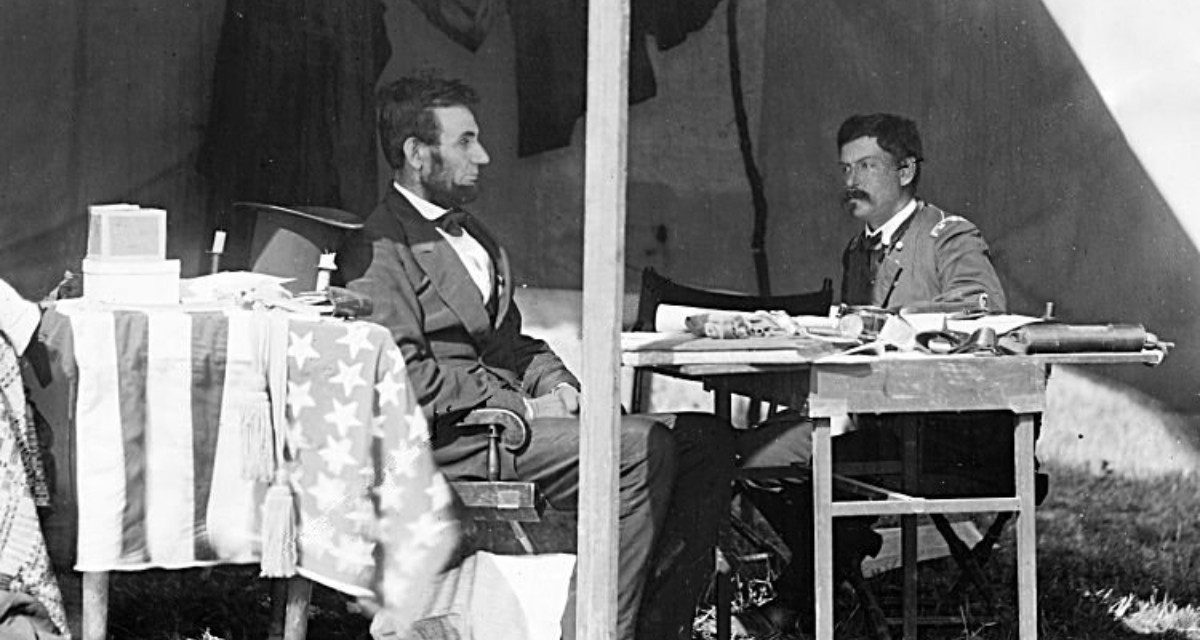

What about McClellan? Was he properly situated to analyze the situation, penetrate the “fog of battle,” and make immediate decisions? Unfortunately, not. Except for two short exceptions, most of the day he spent at his headquarters at the Pry House, one and a half to two miles from the action. At that spot, he was able to view the center portion of the battlefield, but none of either flank. In addition, McClellan developed a disjointed plan of battle, and his army’s leaders suffered from a lack of clearly communicated command relationships—all clear violations of the principles of what today we call Mission Command. The Federal staff system was copied on the French Napoleonic system. Corps d’Armee in Napoleon’s system fought independently. All of McClellan’s corps fought in this way at Antietam. Although the men showed tremendous bravery and junior officers were inspiring, the performance of most of the senior generals of the Federals can be judged as lackluster.

For all intents and purposes, Lee personally managed the crucial fight for the Confederate center. Lee showed himself to be more of an active leader than McClellan, observing firsthand how his troops were deployed, and moving them to reinforce positions he felt were in need of strengthening. He was audacious in the extreme, placing his army with the Potomac river at its back, inviting destruction.

Arguably the best account of the battle is Stephen Sear’s The Landscape Turned Red. In it he says, “The elementary precaution of guarding the army’s left flank with cavalry was ignored, granting Powell Hill the decisive advantage of surprise and position.” The Confederate Army was thereby able to extricate itself from a potentially disastrous defeat. Records prove that the rebels were highly outnumbered at Antietam and needed Maj. Gen. A.P. Hill’s division to make a forced march of seventeen miles to save the day. An aide to Lee commented long after the fighting: “There was a single item in our advantage, but it was an important one. McClellan had brought superior forces to Sharpsburg, but he had also brought himself.”

McClellan had committed barely 50,000 infantry and artillerymen to the contest. A third of his army did not fire a shot. Even at that, his men repeatedly drove the Army of Northern Virginia to the brink of disaster, feats of valor entirely lost on a commander thinking of little beyond staving off his own defeat.

If McClellan was a bold leader who placed himself at the point of the action to better analyze events as they unfolded on the day, if Burnside had flanked the bridge and captured it sooner, if the Federal cavalry was placed correctly and had an active and audacious leader like Stuart—in short, if McClellan commanded a force committed to the exercise of Mission Command—the war may well have been over that day.

Maj. Ronald Roberts is currently attached to the Asymmetric Warfare Group. He has deployed to Iraq with Special Operations Joint Task Force–Operation Inherent Resolve and Afghanistan as a civil affairs officer. Maj. Roberts holds a master’s degree and bachelor’s degree in education from Springfield College, Massachusetts. He has published numerous articles, most notably in the NCO Journal, the Wavell Room, and for the Modern War Institute at West Point.

The views expressed are those of the author and do not reflect the official position of the United States Military Academy, Department of the Army, or Department of Defense.