Editor’s note: This article is the second in a five-part series on educating Army leaders for future war. Read part one here.

The future ain’t what it used to be.

– Yogi Berra

While describing the role of friction in warfare, Carl von Clausewitz wrote that “everything in war is very simple, but the simplest thing is difficult.” Though war has always been and will always be very difficult, changes in the character of warfare over the past two centuries indicate that everything may not be as simple as it once was. For example, the types of problems the Russian military has struggled with during its invasion of Ukraine are not new: logistics, sustainment, achieving surprise, protecting forces, and achieving unified command are all enduring military challenges. Yet new threats from unmanned aircraft, loitering munitions, multispectral sensors, satellite imagery, cyber, and many more emerging technologies have made the successful execution of warfighting functions far more complex than they were on previous battlefields.

The increasing number of variables on the battlefield, increasing range of sensors and weapons systems, and increasing speed of decision-making are evidence of an exponential increase, rather than a linear one, in warfare’s complexity. In fact, Army Research Laboratory chief scientist Alexander Kott developed a formula to demonstrate that growth in the range and destructive capacity of weapons systems over time is exponential. Russian military leaders have proven unable to adapt to a dramatically more complex battlefield, resulting in operational failures and the deaths of senior military leaders. If American military leaders are to fare better in future wars, they must understand the increasing complexity of the battlefield far more than their Russian counterparts.

A better appreciation of the context in which war is fought, the first part of leadership’s paradoxical trinity, requires an examination of both battlefield dynamics and external factors that have impacted war through the past few centuries. The Cynefin framework, described in greater detail below, is used to categorize context. This framework is especially useful not only because it helps make sense of war’s increasing complexity, but also because it explains how different leadership attributes and styles are necessary in different contexts. As war’s character becomes increasingly complex, this framework will help show that the character of leadership must adapt alongside it.

The Cynefin Framework

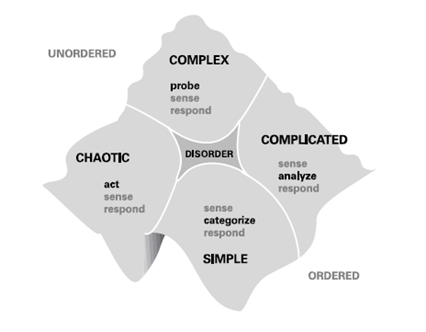

There are many tools available to help make sense of context. Given the dynamic and interactive nature of war, this article employs a model that emerged from complexity science called the Cynefin framework. The Cynefin (pronounced ku-nev-in) framework divides contexts into four separate categories: simple, complicated, complex, and chaotic. As David J. Snowden and Mary E. Boone describe, “Simple and complicated contexts assume an ordered universe, where cause-and-effect relationships are perceptible, and right answers can be determined based on the facts. Complex and chaotic contexts are unordered—there is no immediately apparent relationship between cause and effect.” Simple contexts are characterized by repeating patterns and cause-and-effect relationships that are easy to understand; this context is the realm of what former Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld famously called “known knowns.” For example, the process for mass-producing an existing product has known variables and clear cause-and-effect relationships. Like simple contexts, complicated ones are still mechanical in that there are causal relationships between variables. However, these relationships are more difficult to discover and more numerous than simple contexts, often requiring expertise, making the context the realm of “known unknowns.” A company attempting to innovate on previous products is likely operating in a complicated context.

Unlike the mechanical dynamics of simple and complicated contexts, complex ones are adaptive. The variables and interactions between them are constantly changing, making it difficult even for experts to discern patterns. This realm of “unknown unknowns” is therefore unpredictable and a small action may produce a dramatically outsized result. The COVID pandemic is one example of a complex system, as there were too many variables that were constantly shifting to be able to predict and control exactly how the virus would adapt and spread. Chaotic contexts are shocks with high turbulence and no patterns at all. This realm is relatively rare and usually exists only for a short duration, such as in the immediate aftermath of the terrorist attacks on 9/11.

The Western Way of War: Historically Complicated, not Complex

In his seminal work on the history of military command aptly titled Command, Anthony King equates the function of control to mission management, which is the regulation of forces in time and space. King argues that because battles historically occurred on relatively small and well-defined battlefields, military leaders were historically preoccupied with problems of control rather than problems of command, which includes properly understanding, visualizing, and defining a mission. With mostly clear understandings of what their units were expected to accomplish in war, commanders historically focused their efforts on how to best control their forces on the battlefield. Mission control historically developed around visual and audible signals that leaders used to coordinate maneuvers on the battlefield, but unit structures, processes, and even the size of fronts endured long past the time it was necessary to communicate visually. During Napoleonic warfare, tactical commanders could visually see much of the geographic space they were responsible for and directly control subordinate elements through means like arm signals, flags, whistles, and horns. For example, Napoleon fought the Battle of Austerlitz with four corps averaging around thirteen thousand soldiers each (roughly the size of a twentieth-century Western division) on just a ten-kilometer front—an average of 2,500 meters per corps.

In World War I, French and British doctrine stated that division fronts for units on the offensive extend from 1,500 to 2,500 meters (and about twice that for the defense). New communications technologies like the telephone and telegraph allowed units to operate outside the line of sight from one another. Key weapons technologies like the machine gun created dramatically more lethal battlefields, but organizations struggled to determine the most effective ways to employ those weapons. The shift in the character of warfare from Napoleon to World War I arguably represents a move from simple to complicated contexts. Problematically, it was not only operational concepts that failed to keep pace with new technology and an increasingly complicated character of warfare, but also command philosophies that perpetuated direct managerial control of subordinate units that prevented them from innovating.

The size of a division front expanded to 4,000 to 5,000 meters in World War II. However, the role of a division commander in these conflicts remained remarkably similar to that of Napoleon’s corps commanders a century and a half before, albeit it with improved technology and more lethal weapons systems. Commanders at the division level and below were entirely concerned with matters of control; they primarily made decisions regarding short-term operations that affected a relatively small geographic space. Difficult though these fights were, they remained in the realm of complicated systems that had discernible cause-and-effect relationships.

The increased lethality and range of weapons systems steadily decreased the concentration of forces on the battlefield since Napoleon, but it was not until after World War II that the geographic space tactical units at the division level and below were responsible for began to expand. Moreover, this expansion was modest. British divisions in the 1980s, for example, were doctrinally responsible for fronts ranging from twelve to thirty kilometers and a depth that allowed them to stay in range of division artillery and high-frequency radio communications. After observing the lethality of the 1973 Arab-Israeli War and seeking to combat the mass and range of Soviet weapons systems, the US Army began to place more emphasis on units operating in greater geographic spaces. Its 1982 operations manual, derived from the AirLand Battle concept, describes the need to extend the battlefield, which required decentralized execution of mission orders and the need for units to operate with greater initiative and agility. These ideas were put into practice less than a decade after the first version of the doctrine was published.

The First Gulf War represents an important inflection point in the changing character of warfare. Western armies were still primarily built for massed assaults, but the incorporation of new technologies allowed forces to distribute while still synchronizing the effects of ground forces and those of new domains like space that affected land operations. The front for the 24th Infantry Division, the XVIII Airborne Corps’s main effort, extended forty kilometers and had a depth of advance of 413 kilometers over four days. Operating at greater distances and planning for the effects of new technologies (especially those that used space and electronic warfare capabilities) on ground combat increased the complexity of the war, but military leaders were still focused on mission management rather than mission definition or motivation. The opening stages of the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq continued the dynamics from the First Gulf War—increasingly large battlefields on which commanders synchronized air, space, cyber, maritime, and electronic warfare capabilities with ground operations.

As these post-9/11 wars devolved into irregular conflicts, they challenged Western militaries’ methods of war that relied on a linear order of operations, mass, and concentration. As retired General Stanley McChrystal, who was responsible for major parts of the war efforts in both Iraq and Afghanistan, wrote, “The speed and interdependence of events had produced new dynamics that threatened to overwhelm the time-honored processes and culture [the US military had] built.” Tactical organizations were forced to transition from units designed to fight on a linear front of a battlefield to those that were responsible for a three-dimensional battlespace. Division staffs exploded from around forty personnel in World War II to ten times that number, in some cases topping one thousand people. In most cases, commanders had little problem exercising control over their forces as they faced a materially inferior enemy. Instead, bloated staffs and disconnects between tactical and strategic efforts reflected problems of command—leaders were often unable to properly define their missions and organize their staffs and forces to achieve lasting success.

Although command problems were largely driven by the irregular nature of the post-9/11 wars, the conflicts also provided glimpses of increasingly complex battlefields that will only be amplified during future conventional wars. Army staffs became so large in part because of operations occurring in domains other than land and because staffs had to deal with information that moved at unprecedented speeds. The proliferation of cheap but deadly technology like drones and explosives, an information environment flooded with propaganda and disinformation, hybrid operations between state and nonstate actors, and agile enemies that move faster than traditional Western militaries’ decision-making processes will be regular parts of future warfare. These dynamics will become far more complex and lethal when the adversaries are not relatively weak irregular forces but near-peer state actors with far more resources and capabilities. Leaders in future wars will again need to focus on problems of control, but they may simultaneously be presented with some of the command challenges the past two decades of war revealed. The Army has not developed to simultaneously deal with problems of command and control during the potentially hyperfast and lethal wars of the future.

The Complexity of Future Warfare

Technological changes have not only caused war to expand geographically, but conceptually as well. The need for military leaders to think holistically in terms of five domains as opposed to two is a massive change. Army leaders must understand and plan for effects not just from the ground and air, but also sea, space, and cyberspace, along with the electromagnetic spectrum and information environment. Army leaders will need more intimate knowledge of joint forces and capabilities than ever before. The requirement to orchestrate effects across multiple domains is not just a change to mission management (control), but also a shift in the very definition of what Army missions entail (command). Existing tools and processes will not be adequate for future operations. Army leaders will have to reorganize staffs, develop new skills in themselves and their subordinates, and implement new procedures for mission planning and execution. In short, the complexity of future war will require the Army to reimagine its approach to both command and control.

In the future, war between peer competitors will occur on battlefields that will likely be vast, highly lethal, and for the first time almost completely transparent. It is not only the increasing range, destructiveness, and precision of weapons that will make peer warfare so deadly, but also the arrays of multidomain sensors that will make it nearly impossible for units to obscure their positions. Such a description is not science fiction, as these dynamics were realized in the 2020 Nagorno-Karabakh conflict between Azerbaijan and Armenian-backed Artsakh forces and during Russia’s 2022 escalation of its war in Ukraine. Though Artsakh forces occupied the traditionally advantageous high ground, dug their forces in, and employed physical camouflage, arrays of Azerbaijani sensors detected those forces and allowed them to be quickly destroyed with loitering munitions, drones, and precision fires. To operate on this battlefield, American forces will not only have to improve their ability to mask themselves from sensors, but also have to conduct distributed operations at a scale never before seen. Divisions could be responsible for fronts of several hundred or even several thousand kilometers, orders of magnitude greater than how they operated during the twentieth century. These units will also have to be prepared to operate without persistent communications, as networks will be denied, degraded, intermittently available, and limited.

Sensors and long-range fires are not the only key technologies that will reshape the future battlefield. Autonomous and robotic systems and the employment of tools that leverage artificial intelligence and machine learning at scale will significantly alter the composition and operational methods of military units. Formations must learn to make first contact with machines rather than humans. Reconnaissance, targeting cycles, military deception, logistics, medical treatment, and all other facets of military operations will incorporate robotic systems that have at least some abilities to operate autonomously and even learn. Commanders and staffs will have decision support tools enabled by artificial intelligence and machine learning to help with planning, potentially speeding up and altering the military decision-making process. To leverage these capabilities, the Army must change not only its doctrine and force structure, but also its personnel, training, education, and leader development programs.

More advanced weapons systems and new technologies will reshape how battles unfold, but they will also impact the human and cognitive dimensions of war. Adversaries have not only used propaganda and disinformation to amplify divisions and sow discord in American society, but they have also explicitly targeted members of the military. In the context of an armed conflict, enemies will amplify these efforts and capitalize on deepfake technology to undermine America’s security alliances, erode trust within military formations, and weaken support from the American public. These effects could not only slow decision cycles, which would have lethal consequences, but also erode the public support that is necessary for a democracy to sustain a protracted effort and craft a coherent strategy.

Individually, each of these developments may seem like steps along a linear evolution path. But the net effect of these changes is greater than the sum of its parts, resulting in an exponential increase in the complexity of future war.

Adapting Army Leadership for Complexity

The modern US Army evolved from a force designed to mass forces for two-dimensional fights in the land domain like the Civil War. The advent of military aviation forced Army leaders to operate in a second domain and think three-dimensionally, but Army leaders in World War I, World War II, the Korean War, and the First Gulf War still primarily thought in geospatial terms. Though the Army has changed both between and since these conflicts, elements like staff structures and the exercise of military command have remained remarkably constant. As battlefield tactics and operations shift from relatively concentrated fights on land to broadly distributed forces attempting to synchronize effects in multiple domains that defy spatial thinking, the Army should resist the temptation to revert to its traditional comfort zone of linear, two-dimensional operations. Instead, basic fundamentals should be reexamined, including the principles of war, staff structures, and perhaps most importantly, leadership.

Developing new ways for the Army to operate, organize, and equip will not be effective if the Army does not deliberately train soldiers to lead on complex and dynamic battlefields. Military command historically developed in a top-down, hierarchical model not because commanders simply felt the need to always be in control, but because that style of leadership is the most effective in the simple and complicated contexts in which wars were traditionally fought. However, as warfare moves into the realm of complexity, traditional models of command and control will be insufficient. Snowden and Boone warn that two traps for leaders operating in complexity are the “temptation to fall back into traditional command-and-control management styles” and the “desire for accelerated resolution of problems,” both of which must be avoided in future war.

While the Army’s publication of mission command doctrine is a recognition of the need to shift away from overly centralized management styles of leadership, many Army officers have struggled to break away from the leadership traps Snowden and Boone describe. It is critical for Army leaders to embrace mission command not because it is a superior leadership philosophy, but because it is a necessary adaptation to keep pace with the changing context and character of war. The next article in the series explores the second part of leadership’s paradoxical trinity: traits of leaders themselves. The article will describe specific leadership attributes suited for different contexts in greater detail and analyze some of the Army’s successes and failures in developing leadership attributes suited for more complex wars. As the context of war changes to become more complex, the character of military leadership must adapt as well.

Cole Livieratos is an Army strategist currently assigned to the Directorate of Concepts at Army Futures Command. He holds a PhD in international relations, is a nonresident fellow at the Modern War Institute, and is a term member at the Council on Foreign Relations. Follow him on Twitter @LiveCole1.

The views expressed are those of the author and do not reflect the official position of the United States Military Academy, Army Futures Command, Department of the Army, or Department of Defense.

Image credit: Sgt. Timothy Hamlin, US Army

Fully agree, and centralized states like Russia simply cannot compete conventionally and/or operationally and tactically with the West and our populist (including video game) technology – coupled with democratically delegating mission command authority doctrine which promotes such initiative as we have seen on the Ukraine battlefield.

HOWEVER, strategically/intercontinentally/orbitally this complexity is terminally (as in virtually suicidally) *dangerous*: strategic nuclear/WMD mass death&destruction weapons systems are infinitely more powerful, instantaneous, and automatically triggered by systems like Russia's Dead Hand.

Russia unable to compete with us in conventional and/or hybrid war now, I started my 3May22 column (posted by Yahoo! both under News and Yahoo! Finance now), "Lou Coatney: Russia now left with no choice but nuclear war." citing this terminal strategic peril, and Henry Kissinger began his 10May22 Financial Times interview exactly the same way, except using the term "automaticity."

(Senator Don Nickles (in the Senate 1999 Kosovo war powers resolution floor debate), I (in American academia on H-Diplo on 14May99), and Henry (in the 31May99 Newsweek) all blew the whistle on Rambouillet App. B, so I suspect Henry had read my Yahoo! article.)

War has become too dangerous in all respects at all levels – especially the ultimate one – and if we don't instead start pursuing the only alternative – international peace and close cooperation – we're confronted with the specter of mass suicide of many billions of innocent people, if not most higher mammalian life itself.

"… dangerous: far more than during the nearly terminal Cuban Missile Crisis, strategic nuclear/WMD …"

An Edit ability would be most helpful, MWI.