During planning for what became Operation Uphold Democracy in Haiti in 1994, a prescient conversation occurred between planners from United States Atlantic Command and members of the Department of Justice. Despite establishing the International Criminal Investigative Training Assistance Program under the Department of Justice to train a new Haitian police force, when told of how the political-military plan envisioned the department’s execution of the operation, the Justice representative stated that the department “could not handle the mission.” At the last minute, an Army infantry battalion was handed the responsibility to train, advise, and assist a newly created Haitian police force. This foreshadowed what would become the standard during America’s post-9/11 wars in Iraq and Afghanistan—infantry and other combat arms units converted to advisors in an ad hoc fashion.

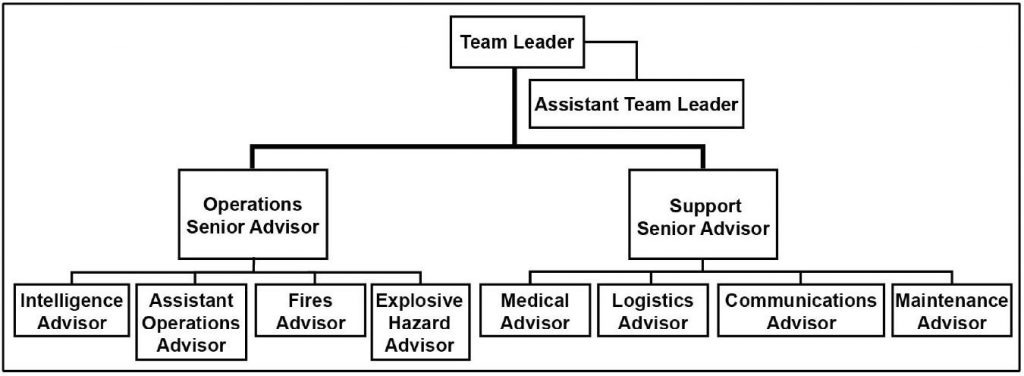

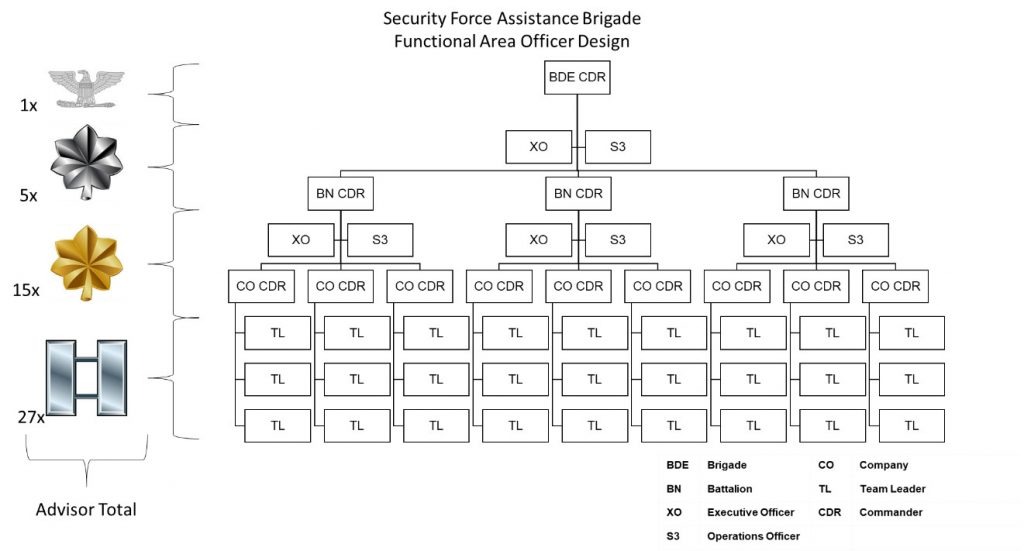

That would begin to change with the US Army’s new security force assistance brigades (SFABs), which are designed to provide conventional force training, advice, and assistance to foreign security forces. To that end, SFAB advisors are formed into twelve-soldier teams, designed to parallel the skills of a battalion and higher staff, with specialists in combat operations and support functions. This diverse team is designed to survive on its own, working in full partnership with a foreign battalion or brigade’s leadership dispersed throughout the battlefield without US support while providing critical linkage back to the joint force for partner-nation battle tracking, combat employment, allocation of supporting artillery and aircraft. The team also conducts assessments of the partner force’s capability to adjust US policy goals in the region.

Advising team (Source: Army Techniques Publication 3-96.1, Security Force Assistance Brigade)

Besides enhancing foreign internal defense lines of efforts and enabling the US military to establish new foreign security forces, SFABs reduce the burden on brigade combat teams, which are poorly organized for advisor missions. SFABs have deployed to Afghanistan and Iraq, but their role in other regions—including the areas of responsibility of Africa Command and Southern Command—is set to expand. Despite this new focus outside of advising missions solely in Afghanistan and Iraq, the Army’s assignment and training process for advisors has no regional focus and loses trained advisors after a short utilization period.

The advisor team fills an important capability gap, allowing US conventional forces to concentrate solely on readiness, deterrence, and ultimately combat operations. It preserves the officer and senior noncommissioned officer ranks in these units by not pulling them away to train local nationals as has often happened in Iraq and Afghanistan. Given the importance of this mission, the Army should consider professionalizing this cadre of advisors by developing a functional area assignment for advising that would increase assignment longevity and advisor skills instead of the form it currently takes, as a broadening assignment of less than three operational years.

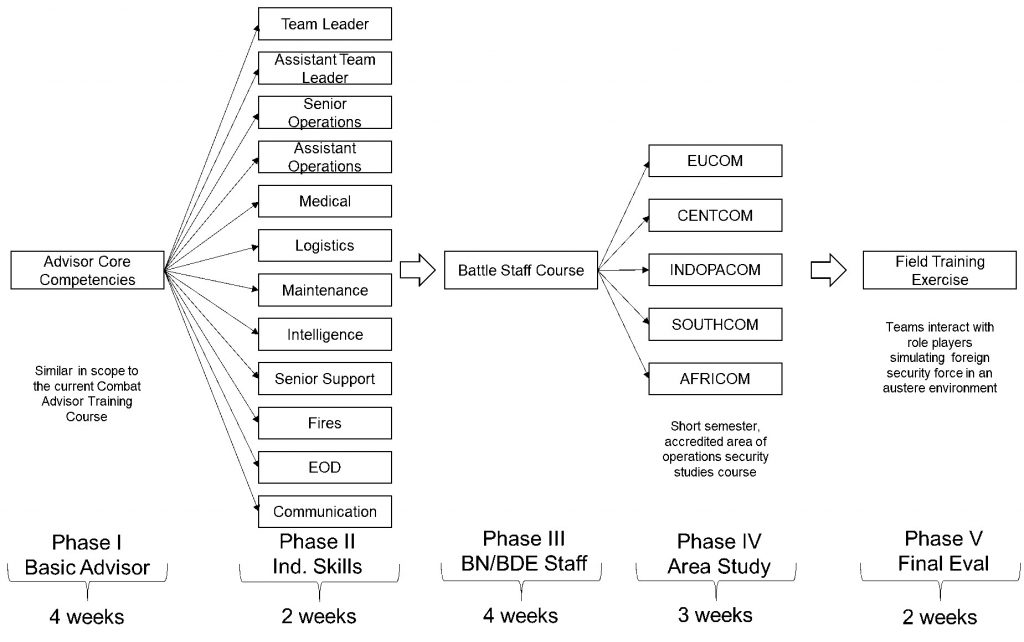

In the current assignments process, those interested in becoming advisors undergo a hiring process—for noncommissioned officers, a three-day assessment at Fort Bragg, North Carolina, and for officers, interviews with the brigade and battalion commanders under whom they would serve if selected. Following selection, prospective advisors all attend a four-week Combat Advisor Training Course, taught at the Military Advisor Training Academy, located at Fort Benning, Georgia. This course teaches each cohort, the members of which range from specialists (E-4) to lieutenant colonel (O-5), collectively—which is an exceedingly wide array of skill levels and years of professional service. Following graduation, each advisor is assigned an additional skill identifier that marks them as advisor qualified.

The Combat Advisor Training Course offers only a rudimentary advising curriculum. Given the large breadth of ranks needing to be trained in the four weeks, training is limited to blocks of instruction on employing an interpreter, cross-cultural awareness, and conducting training assessments, while tactical instruction focuses on survivability skills like medical treatment, employment of indirect fire assets, and land navigation. The Army is able to mitigate the risk of this short, mile-wide-but-inch-deep certification because the majority of those assigned have had multiple deployments in their careers, with most having at least some experience in either training or advising Iraqi or Afghan counterparts in the past. As operations wind down in Afghanistan and Iraq, this reliance on previous experience in advising foreign security forces will evaporate quickly.

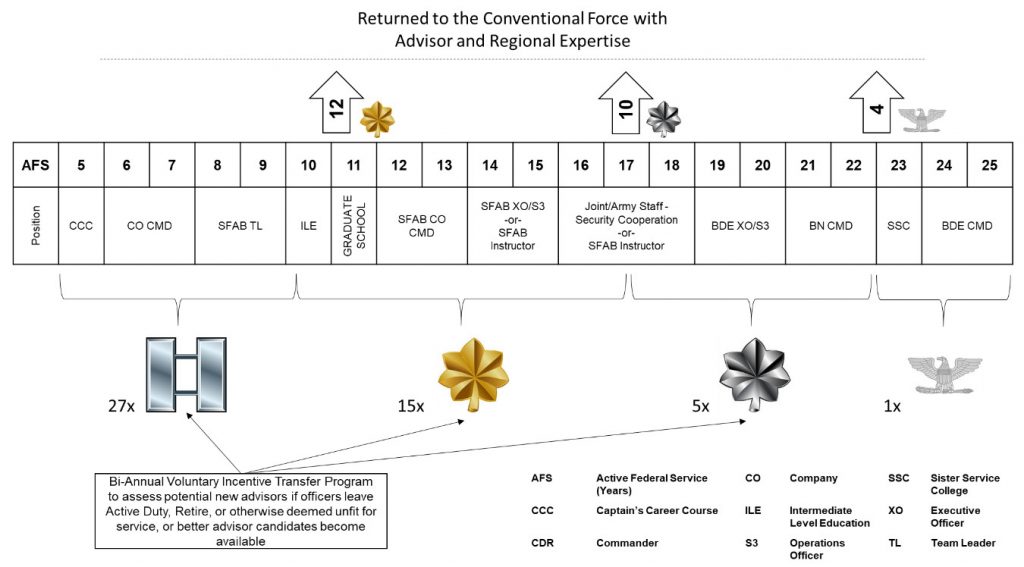

Rather than relying on a brief, four-week course in order to maximize utilization during a broadening assignment, the Army should consider making advisor positions a functional area for officers. Rather than returning to the regular assignments process following their three-year assignment, functional area officers are retained and progress within that functional designation. This change, and an accompanying advisor secondary military occupational specialty for enlisted personnel, would allow the Army to maintain a competent core of advisors without impacting their promotion potential and career progression.

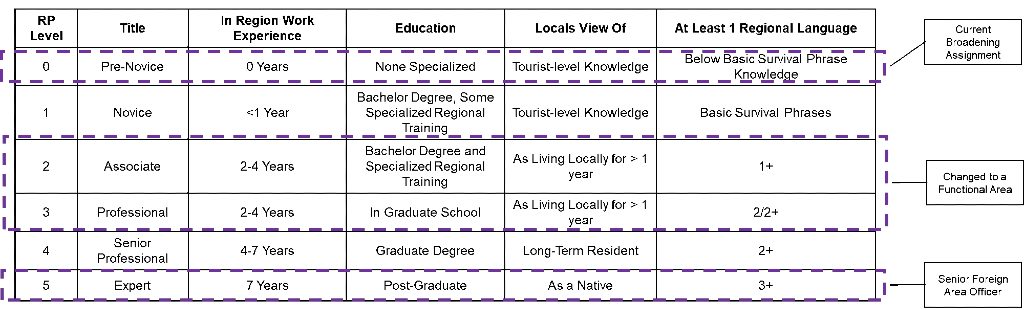

Given that advisors are required to interact on a regular basis with members of a foreign security force, it would make sense for them to be assigned and developed according to DoD policy on the management of the Defense Language, Regional Expertise, and Culture Program. That program includes a description of various levels of regional proficiency. If the Army adopts a functional area model for advisors—in tandem with plans to align each SFAB with a geographic combatant command—there is significant potential for the development of a cadre of advisors that are regionally proficient at level 2 (Associate) and level 3 (Professional) by the time they reach senior field-grade assignments (See figure below). As it stands right now, there is no regional proficiency selection or assignment process for an SFAB broadening assignment, meaning officers and noncommissioned officers at regional proficiency level 0 (Pre-Novice), with essentially no experience or formal education in the region at all, are assigned as advisors.

Summary of regional proficiency levels, as described in Department of Defense Instruction 5160.70, “Management of the Defense Language, Regional Expertise, and Culture (LREC) Program.”

In this functional area model for officers, the selection process would select from pools of captains following their time in a key developmental position. While the figure below only focuses on combat arms advisors whose key developmental position is company command, a similar process would be made for operational support positions. Each brigade would have twenty-seven combat advisor teams led by a functional area advisor. As cohorts of officers progress through the ranks, the majority would be returned to their original branch or leave the service through normal attrition, while high performers with an aptitude for advising would assume positions of greater authority. This accomplishes two major objectives. First, it returns to the brigade combat team a cohort of officers with regional experience that will be invaluable in future crisis response planning and execution. Second, and more importantly, it provides a retention capability for the advisor corps, in a specific regional specialty, similar to the foreign area officer corps. As advisors progress, they would be able to complete advanced schooling in regional and international affairs that would professionalize the corps over time. Supplemental positions not of an advising nature, like a company executive officer, can remain part of the regular assignments process.

The functional area assignments process allows advisors to become regionally focused and deploy to the same area of operations over the course of their career. This would enable officers to understand the human terrain of the area, develop military-to-military relationships at the tactical level, and build on previous successes. An SFAB, fielded with functional area advisors, regionally aligned to AFRICOM, for example, could send the same cohorts of officers to advise training and operations in the Sahel consistently, with advisors and foreign security partners working together as they progress through the ranks.

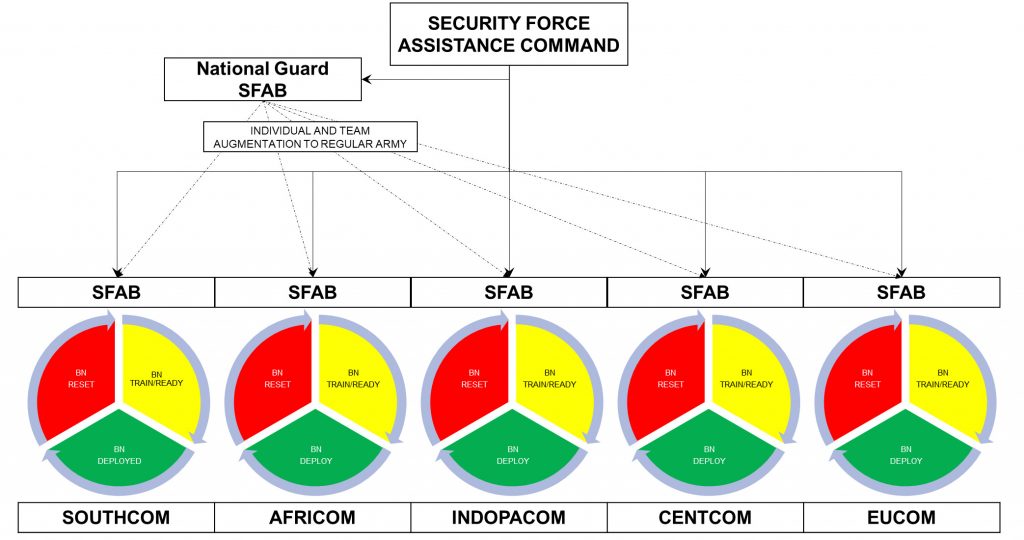

The figure below is based on the Army’s old Army Force Generation model, but it could be applied to SFABs with regional alignment. Doing so would allow a three-battalion SFAB to maintain one battalion and its twenty-seven advisor teams deployed to a region, one battalion conducting reset, and one battalion in a trained and ready phase, capable of surging support in times of crisis. With five regionally aligned active duty brigades, SFABs would have a persistent forward presence. The Army’s National Guard SFAB, rather than an independently deployable brigade, would be an auxiliary and reserve force from which each brigade would be able to request augmented support if the manpower requirement becomes onerous for any particular region or a crisis erupts. Rather than a whole brigade focused on the region, the National Guard SFAB would develop advisor teams and individuals that were regionally focused; operating more as a strategic reserve than an operational force.

While a functional area assignments process would impact the SFABs’ officer corps, special assignment procedures for noncommissioned officers with a secondary military occupational specialty would allow for enlisted personnel to progress as advisors without negatively impacting their promotion potential. Because the current assignments process is a broadening assignment, much like their officer counterparts, enlisted personnel are returned to the conventional force in order to fill key developmental positions for their rank and primary specialty and be promotable. As a secondary specialty, advisors would attend specific geographic combatant command and advisor training. Additionally, a fully accredited battle staff course component will likely be necessary to give noncommissioned officers greater exposure staff functions for their specialty at the battalion level and above. Incorporating a battle staff course into the training pipeline ensures that all members of the advising team are capable of understanding and advising planning at echelons above their previous competency.

Potential advisor qualification pipeline in a functional area/secondary military occupational specialty system.

This proposal—adopting functional area and secondary military occupational specialty assignments—would require significant investment. It would also need buy-in from geographic combatant commanders. Each commander would need to see the value in having a reliable pool of well-trained advisors. Without this, and funding allocated by Congress, it would be moot to develop advising as a functional area. If combatant commanders do see the value, as seems to be the case, SFABs would provide a real advise-and-assist capability, rather than training or advising forces in an ad hoc manner with brigade combat teams or with advisors with limited cultural or staff knowledge. Combatant commanders would be able to call on a contingent of regionally astute and tactically capable advisors to deploy to the same area of operations repeatedly, reducing the time required to achieve foreign security force goals.

The proposed change in assignments process offers four distinct advantages. First, it increases the Army’s ability to meet international security cooperation agreements at a significantly reduced cost in dollars and readiness. Train-and-advise missions can be accomplished with relatively fewer individuals and a smaller equipment package, and a constant development pathway extends beyond a single brigade rotation to a theater. It also alleviates the need to deploy brigade combat teams, thereby increasing operational readiness by maintaining more brigades available for decisive-action deployments if required.

Second, it enhances partnerships in an era when the Army no longer goes to war alone. The National Defense Strategy specifically describes strengthening alliances and attracting new partners as a strategic priority, and redesigning the SFAB assignments process directly impacts this priority. Besides the enhanced security cooperation that would be accomplished with more regionally attuned advisors, during decisive-action operations with a combined force the SFABs could prove invaluable. Rather than having to give up staff horsepower to serve as liaison officers during a crisis, the Army could now provide advisor teams that have habitual training and advising relationships with countries contributing to the coalition at all echelons. The wide array of talent provided by the advisor team can impact everything from coalition communication to intelligence dissemination to indirect fire and close air support. Interoperability is always a challenge in these environments; advisor teams, self-contained and backed by significant communications capability, can tie into every staff function of a coalition partner or ally to synchronize operations.

Third, the new assignments process allows for the retention of combat arms and support personnel outside of the current brigade combat team structure. By retaining mid-career officers and noncommissioned officers, the Army has the ability to rapidly expand and increase the number of its brigade combat teams in short order. Essentially, SFABs can rapidly absorb newly recruited personnel to become full brigade combat teams as the majority of key leadership positions are already filled. Each SFAB battalion essentially has almost a full brigade’s complement of combat arms officers. While this has been touted as a feature virtually since SFABs were first proposed, the current broadening assignment model creates limitations. In order to create the numerous post–key developmental positions the SFABs require, and do so continuously, key developmental position length is curtailed in order to meet the demand. Instead, by offering a functional area to grow and retain officers, the Army will no longer have to rapidly certify officers as having completed their time in key developmental positions to be available for SFABs. This stabilization in a functional area enables greater training time available by reducing the numbers of permanent changes of station.

Finally, it increases the Army’s regional competency. While this commentary has focused solely on the advisor assignments process and the retention of trained personnel, it also redistributes back to the force officers and enlisted personnel with an increased regional proficiency that have a better understanding of allies and partners. This assignments process would return twelve captains from each brigade to the conventional force after their team leader time. Having been exposed to regional tactics, techniques, and procedures, completed advisor rotations to foreign countries, and developed an enhanced understanding of planning at battalion and brigade level, this assignments process pays huge dividends to the conventional force, as well.

Because the SFABs are still being constituted, treating them as broadening assignments makes sense for the time being. These organizations have a proven requirement to meet national objectives and need to be utilized, so there is a need to rapidly fill their ranks. However, the functional area and secondary specialty assignments process described above should be instituted over the coming years as advisory experience from years of deployments to Afghanistan and Iraq increasingly evaporates from the force. If the Army wants to transition the SFAB from an organization that—outside of longer deployments in Afghanistan and Iraq—merely provides short-duration training packages like a three-week vehicle-recovery course for foreign partners into a true cadre of combat and sustainment advisors that have a persistent foreign presence, it needs to radically rethink the assignments and education process for the position. After years of deployments to Iraq and Afghanistan, the Army recognizes that there is a mission requirement to have an advisor corps. Establishing the SFABs is an important first step. The next one should be a fundamental reassessment of its assignment, education, and fielding model.

Jon Tishman is a captain in the US Army currently assigned as an advisor team leader with 4th Security Force Assistance Brigade. Jon has deployed four times to Iraq and Afghanistan. During a break in service Jon lived in Australia selling military equipment to foreign militaries in the Australasia region. He commissioned from the Virginia Military Institute and is pursuing a master’s degree in international relations.

The views expressed are those of the author and do not reflect the official position of the United States Military Academy, Department of the Army, or Department of Defense.

Image credit: 2nd SFAB

An excellent, thoughtful and comprehensive article that hopefully will generate much discussion and consideration. The U.S. Army has had multiple excursions in this area over its history the more modern versions being the work assisting in the forming of the Philippine Army, work in South Korea after WWII, the Military Assistance Advisory Groups of the 1950s, the Military Assistance Advisors in Viet Nam, aspects of Special Forces operations forward to the excursions in this area over the last 20 years. One might argue that even aspects of the KATUSA program, the Army National Guard and Army Reserve active Army advisor programs that operated for most of the 20th Century and the work with senior Army ROTC programs on college and university campuses across the U.S. are related to skill sets necessary to be effective in operations of this type. The challenge to maintaining such operational capability and organizations as a sustaining element of the force will be an understanding of its relevancy by policy and lawmakers and senior Army and civilian leaders. As well, the ability of the Army to develop and sustain the necessary KSAs in the units to be effective and assure that such duty is aligned with the ability of officers and NCOs assigned to remain viable and competitive in the Army, that assignment to such duty does not prove a path to nowhere professionally for the professionals assigned to such duty, will be critical to success. The author provides some very interesting discussion and proposals in these areas. My sense from extended Army experience, study and observation has emphasized the importance of the Army being capable in this area of operations and able to adapt its capabilities to an ever changing environment. This was a very good read and I recommend it.

Great article by CPT Tishman- he provides some great insights on the importance of regional understanding. As 5th SFAB works toward our alignment with INDOPACOM we are seeing the tremendous value of persistent presence by trained advisors inside the contact layer where strategic competition is most acute. This is where we are headed.

We have also learned that the greatest skill that our partners in the INDOPACIFIC want from us is not cultural savvy or language training but mastery of warfighting skills at echelon. As we partner with very capable militaries like the Thai and Philippines Armies they expect our advisors to arrive with recent, relevant experience from either combat or our CTCs. This is our competitive advantage over alternative partners like the Russians and Chinese. This expertise must be learned and built in conventional units. This is why a CPT serving in an SFAB must return to a tactical BN as an S3 or XO before he can continue to serve again in an SFAB. A foreign Brigade staff is not likely to see value in being mentored by a senior Major whose last operational assignment in the US conventional force was as a company commander. Likewise, it is imperative that our SFAB BN and BDE CDRs have recent experience commanding BNs and BDEs in the conventional force. This gives them the credibility that they need to properly advise their foreign partners.

We completely agree that cultural and language training will always be valuable but we need to be careful not to try to model SFABs too close to our SF brothers. At 5th SFAB, we spend a lot of time working with 1SFG(A) and deeply admire the depth of their regional expertise. They are the first to tell us that no one in their formation has expertise on how to build a battalion maintenance program or plan a brigade integrated defense. This is where they see our skills sets as most valuable. By complementing their deep regional expertise with our recent warfighting experience, we think we are equipping the INDOPACOM commander with the right tools to execute the National Defense Strategy.

COL Curt Taylor

Commander, 5th SFAB

Pretty obvious that the author has no concept of Foreign Internal Defense (FID), nor that FID is a regularly assigned mission to the US Army Special Forces (18 series) as they are masters of FID.

FID is broad. SFA is a line of effort. SFABs get after things SOF don't, like COL Taylor mentions above, such as logistics.

The single line regarding FID "Besides enhancing foreign internal defense lines of efforts" is lifted directly from the ATP regarding SFA, of which the SFABs are a component, can set conditions for FID

Per ATP 3-96.1

1-34. SFA activities support efforts by increasing the capacity and capability of partner security forces. Foreign internal defense directly supports activities that involve organizing, training, equipping, rebuilding, advising, and assisting the FSF to combat internal threats. The SFA can help set conditions for the conduct of the foreign internal defense when there are external threats that the FSF does not have

the capability or capacity to mitigate or overcome. Foreign internal defense includes indirect support,

direct support (not involving U.S. combat operations), and combat operations. (See JP 3-22 and ATP 3-

05.2.)

A well written and thoughtful article on the SFAB, but I have to side with COL Taylor on the personnel management and development of our Officers. When we first started the SFAB, we brainstormed this exact concept. Our counterparts expect Officers and NCO Advisors to arrive with current experience in the force. But this obviously comes at a cost which you pointed out. The issue which we run into is knowledge management; we cycle our skilled leaders back into the force when their time is complete here. I directly feel the pain from this as I was the first Team Leader to arrive at 1st SFAB back in June of 2017. I'm transitioning out of my position as I head to ILE, but my replacement will not be on ground until later in the year. Our transition is difficult, but manageable with consistent communication and product exchanges.

From my small foxhole, I would change our MTOE slightly to accommodate a COCOM aligned persistent mission. I recommend restructuring our 6th Battalion from an advisory role to a dedicated support battalion. Our limited personnel and staff struggle at times balancing the role of advising and providing support to our subordinate teams. The logistical advising can be accomplished by utilizing the LATs (logistical advisory teams) which proved very effective during our Afghanistan tour. I could go on and on with my recommendations based upon my experience here, but I'll save you the trouble. Again, thank you for pointing out critical training which us as Advisors must take into consideration in preparation for our next mission.

MAJ Joe Fontana

Team Leader, 1st SFAB

Very thought-provoking article, Jon!

The SFABs have the ability to fill many gaps where our current conventional force models are insufficient.

As COL Taylor said, the tactical expertise from a line BN will serve to ensure that Advisors are sharing the most up-to-date doctrine and “lessons learned” which is ultimately what our allies and partner forces seek.

I think the idea of the SFAB has been better than the execution to this point. I love this article, but I think the SFABs may have to become a regular assignment in the future or they will eventually go away. I'm in 3SFAB, and I'm seeing problems with recruting; when I first arrived to the unit was shocked to see how many people were not KD complete and had not deployed. My peers aren't interested in coming either.

I think a change in culture would help us; there seems to be a constant default to traditional BCT thinking that should be modified to suit the SFAB. We are not special per se, but we are specialized. For example, we were constantly told that we were already familiar with advising (through being squad leaders, PLs, Commanders, etc) and instead of focusing on "softer" skills, we built to live fire exercises that had little to do with actual advising. This led to logistics advisors who were not famliiar with ANDSF forms, processes, etc when we went to JRTC. Reverting 6th BN to a traditional BSB role may not be a good move either, as my 6th BN is currently handling the bulk of the advising in country right now. They struggled with trying to advise and support in the rear. I think the SFABs are an important piece to the Army going forward and I'd love to see them mature in the right direction; I'm just not sure they are.

The current SFAB organization is built to operate at the BN/BDE staff level. However, there is still a gap at the lower echelons. A 12-person advising team might consist of 4-5 combat arms Soldiers. That's not very many to work directly with multiple companies within a battalion, let alone at the Platoon or squad level.

I recently conducted an SFA mission at a company level using approximately 10-15 Soldiers and still felt like it wasn't enough – though most of them were not NCOs as we're a regular light infantry company. That doesn't even include the other Soldiers in my company providing the day-to-day logistical and administrative support and the ability to surge more for larger events like live-fire ranges or conducting multiple training/evaluation lanes. I definitely saw a need for those other specialized skills like logistics and maintenance that we didn't have the expertise in. That's something an SFAB company brings, but they lack the sheer numbers to get down to the Soldier/NCO level. One of the greatest strengths of the US military is our NCO Corps. Only two operations NCOs in an advising team does not allow those NCOs to effectively interact with the dozens of squad leaders and platoon sergeants (assuming the partner nation even has those same positions – which not all do) that would be in a battalion.

If we look at the potential SFAB missions across the different regions it might make sense for one region to focus more on lower echelons while another focuses on those higher echelons as they have greater proficiency at the platoon and company level. A one-size fits all MTOE doesn't provide a lot of flexibility to task organize without affecting the ability to regularly rotate.