“Joe, I got this.” As I took the flight controls from my PIC—my pilot in command—I was eager to shine. Up until this point in my deployment, I had received strong accolades from the senior pilots in the company. I studied the aircraft’s operating manuals, flew on increasingly risky missions, and sought every opportunity to earn respect from the company’s aviators. I wanted them to know that I was ready for their blessing to become a PIC. As expectations increased, I was flattered—and eager to meet and exceed those expectations.

On this particular nighttime mission, Joe had just aborted a dangerous landing into a dusty pick-up zone (PZ). As I peered through my night vision goggles during his attempted landing, I never lost sight of the ground. As such, I felt like Joe’s decision to abort was premature. Joe was a cautious pilot, and his caution gave me an opportunity to exceed the expectations that had been growing on my shoulders. Joe offered me the flight controls as we orbited to attempt a second landing into the PZ.

With the controls in my hands, I peered out of my night vision goggles as we approached the landing area. We yelled out the distance and airspeed as we drew closer to the objective: 70 knots, 700 meters . . . 50 knots, 300 meters . . . 30 knots, 200 meters . . . 30 knots, 100 meters. “Commit commit commit!” I announced through the ICS—the internal intercom we used to communicate. My hands nervously gripped the cyclic and collective as the ground came closer and closer in sight. I hunted for an object to focus on as we came closer to impact. “I have the ground in sight . . . I have the ground in sight,” I repeated, anxiously awaiting the split second when the dust cloud would obscure my view. As the dust entered my vision, for what should have been less than a second, I hesitated. Crew chiefs yelled over the ICS: “Sir, do you have the ground? Sir!!” I didn’t respond. As I “hunted” for the ground with my flight controls, we finally hit the dusty surface, and the aircraft slid laterally and jolted back and forth before finally coming to a rest. We were lucky to get through the landing unscathed, and I was humiliated by my butchered landing attempt. Joe broke the ice in the air: “Sir . . . that was a close call! What were you thinking!?”

On that dusty PZ in Afghanistan, I let high expectations and my eagerness to exceed them get the best of me. These two leadership ideas—that high expectations can bring the best out of others and that good leaders find ways to exceed expectations—were and still are tenets in my own leadership philosophy. But the landing with Joe provided a necessary demonstration of not only the power, but also the limits, of these tenets.

The Power of Expectations

Most leaders would agree that high expectations can bring out the best of the people in an organization. When an organization holds itself to high standards, people respond. In 1956, Robert Rosenthal conducted an experiment in an elementary school that demonstrated the power of expectations. He provided teachers with a list of “top” students; little did the teachers know that the top students were simply randomly selected amongst the student population. When Rosenthal captured performance metrics later in the year, the randomly assigned “top” students had shined. High expectations from teachers created better outcomes for students; with a higher bar, students rose to the occasion. This self-fulfilling prophecy, known now as the Pygmalion effect, provides a psychological case for setting high expectations for yourself and the people you lead. Knowing that somebody believes in you enough to raise the bar can inspire you towards meeting and exceeding those lofty expectations.

How leaders create value. When high expectations are placed on a leader, how do they respond? The field of finance provides a powerful lens through which to examine this question. In finance, good leaders create value, and creating value directly relates to expectations. In his book, The Wisdom of Finance, Harvard professor Mihir Desai provides a simple recipe for what value creation means in the financial context. Leaders create value when they “surpass expected returns” of investors. An investor’s expected return is captured in a discount rate, which is an estimate of the return that an investor would receive on a similarly risky project. As a leader, if you deliver a return that is less than the investor would have received otherwise, you’ve destroyed value. If you meet expectations, you haven’t created any more value than the investor would have gained investing in another project with similar risk. If you deliver returns that exceed the investor’s expectations, then you’ve added value. Put simply, leaders create value when they exceed expectations.

The combination of these two points—setting high expectations and trying to exceed them—is at the heart of the “winning culture” mindset that so many leaders, including myself, espouse. Raising the bar creates a new norm; instead aiming for a C, value-creators aim for a B. And once everybody starts aiming for a B, that becomes a new norm, and value-creators aim for an A. This intuition cascades towards excellence, but taken to the extreme, it can also cascade in a dangerous direction.

Limits to this logic. As my experience in the dusty PZ in Afghanistan demonstrates, high expectations have limits. A 2015 Harvard Business Review article describes these limits in a business context. High expectations can pressure business leaders to “make investments that encourage markets to believe that the firm has value-creating potential, even if they know that those investments will ultimately fall short.” Faced with higher expectations, business leaders chase opportunities with higher returns, but projects with higher returns also have higher risks. Citing the work of Michael Jensen and cautionary case studies of companies including Citigroup and Valeant Pharmaceuticals, the article highlights the “agency costs” associated with inflated expectations. These costs include shortsighted, unethical, and even unlawful decisions. And the idea of providing safety valves—off-ramps that allow expectations to adjust downward according to market and business conditions—is not an easy pill to swallow. It wouldn’t have been easy for me to swallow if the senior pilots told me that I wasn’t as good as they thought that I was. Similarly, it isn’t easy for a business to hear that it’s not worth as much as investors originally expected. Powering down an expectation can hurt.

Getting the Most out of High Expectations

Organizational norms. Given these limits, how can organizations expect big things in a productive way? When I pose this question to cadets at West Point, most respond with the idea of establishing organizational norms. Whether citing laws and operating procedures or values and codes of conduct, these types of norms provide a necessary ethical, legal, and operational constraint. At West Point, the cadet honor code, Army values, Uniform Code of Military Justice, and myriad of operation procedures all serve in this checking capacity.

In addition to this idea of checking value-seeking behavior with norms, finance provides additional insights towards how to get the most out of high expectations.

Knowing your strike zone. When describing the recipe for sound investing, Warren Buffet often cites Hall of Fame baseball slugger Ted Williams’s book, The Science of Hitting, and the idea of a “circle of competence.” Just as good hitters swing at pitches that they know they can hit, good investors swing where their competencies lie. The same should hold true for individuals and leaders. Resist the urge to exceed every expectation, but when you get a pitch that you can handle, try to hit it over the fence.

Whether on the receiving or delivering end of high expectations, this granular approach to expectations requires patience, self-awareness, and, perhaps most importantly, an organizational culture with psychological safety. A recent study by Google found that psychological safety was the leading indicator of high-performing teams. The study references the work of Harvard professor Amy Edmonson. Edmonson defines psychological safety as a team member’s belief about “how others will respond when one puts oneself on the line, such as by asking a question, seeking feedback, reporting a mistake, or proposing a new idea.” In other words, these are places where people feel like they can take swings—take risks—but also feel comfortable holding off on a pitch.

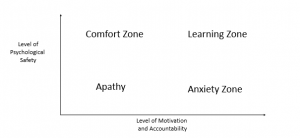

Psychological safety isn’t at odds with high expectations. In her TED Talk on the topic, Edmondson describes the best organizations as those that combine the two—a high level of motivation and accountability with a high level of psychological safety, as illustrated in the “Learning Zone” in the figure below.

An organization in the “Learning Zone” is clearly one where batters try to hit homeruns. The difference is that batters in these types of organizations don’t swing at every pitch. They use successes and mistakes to develop their own, unique circle of competence. And their leaders provide them with the space and confidence to do so.

A Paradoxical Awareness. When I think back to my botched landing with Joe, I certainly had high expectations placed on me. But I also didn’t appreciate the level of psychological safety that existed in my company at the time. Had I aborted the landing, I would have demonstrated a self-awareness in my own abilities—an awareness that Joe and my two crew chiefs would have surely appreciated.

A few years later, I was deployed to Afghanistan again, now serving as a company commander and PIC. On a summer afternoon, I took one of my platoon leaders out on a training mission to practice dust landings. We practiced in progressively dustier conditions, and my platoon leader, now striving to earn his PIC status, seemed close to mastering these tricky landings. Near the end of our training mission, I landed into a very dusty landing zone, and then transferred the controls to my platoon leader, eager to see him stick a tough landing. “Sir, I don’t feel comfortable with this one.” We decided to call in quits on our training mission.

Later that night, over dinner with our battalion’s senior pilot, I shared this story. His response stuck with me. “It sounds like your platoon leader’s ready to be a PIC.” My platoon leader knew his circle of competence, and he wasn’t afraid to hold back on a pitch that he didn’t think he could hit. Paradoxically, his awareness and vulnerability to say “I can’t do this” said more about his readiness as a PIC than any successful landing would have.

To get the most out of high expectations, organizations must have strong norms—ethical, legal, and operational. But perhaps just as importantly, organizations must create an environment where batters understand their unique circle of competence and know when to hold off—or swing—at a pitch.

Sgt. 1st Class Stephanie Carl, US Army

Thank you for your leadership lessons. Very informative and interesting. I take a lot of information from here https://bumblephone.com/category/military-leadership/ , but your lessons are really good.