Ask the average division staff officer how many brigade combat teams it takes to seize a city of one hundred thousand people crammed into twenty-five square kilometers and you will likely get a blank stare or a wild guess. This reaction comes despite the realities of the modern world: rapid urbanization with over half the global population currently living in cities and estimates that this figure will climb to nearly 70 percent by 2050; the complexity of dense urban areas that make them labyrinths of structures, people, the electromagnetic spectrum, and infrastructure; and the fact that most conflicts in the last twenty years—from Ukraine to Syria and Iraq to Nagorno-Karabakh—have seen significant fighting in cities.

Although most infantry soldiers can execute Battle Drill 6 (Enter and Clear a Room), few staff officers are prepared to plan and execute large-scale combat operations in dense urban terrain. Famously during the Vietnam War, Lt. Col. Ernie Cheatham, upon learning that he was going to lead his battalion of Marines into urban combat the following day in Hue, found and read two city-fighting manuals that recommended staying off the streets and moving forward by blasting holes in walls. Today’s staff officers need to do better than “cramming” the night before the big exam.

That is why the 40th Infantry Division, California Army National Guard, decided to create the US Army’s first formal course designed specifically to improve staff planners’ ability to analyze and plan large-scale combat operations in urban environments with populations from fifty thousand to over ten million. The idea came from an Urban Warfare Project Podcast episode and was executed jointly by the authors with a great deal of help from the division’s staff officers, noncommissioned officers, and soldiers.

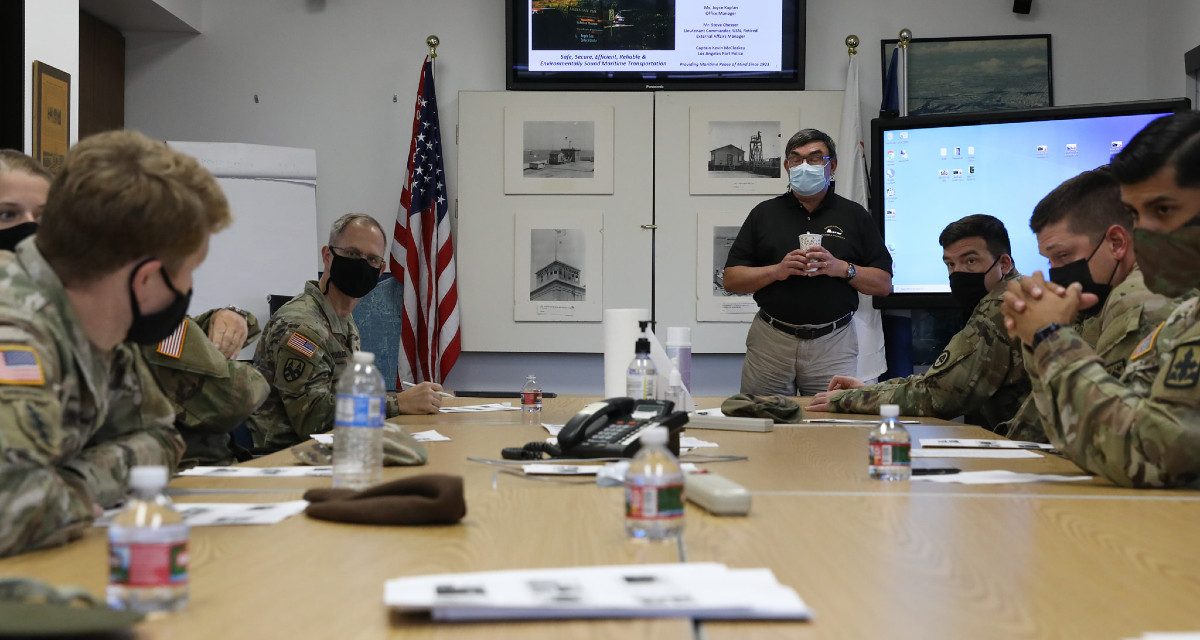

We ran the first class from October 17 to October 23, 2021 at Joint Forces Training Base in Los Alamitos, California with a class size of nearly fifty students. The student population included Army officers and noncommissioned officers from all three components (National Guard, active duty, Army Reserve) and international military personnel. The instructors included members of the California National Guard, National Training Center cadre, and many of the world’s leading urban operations experts such John Spencer, Dr. David Kilcullen, Dr. Jacob Stoil, Dr. Louis DiMarco, Ms. Sahr Muhammedally and many others.

We conducted an after-action review (AAR) at the end of every day and at the end of the course. We learned, and continue to learn, numerous lessons that were recorded in our AARs. The most important thing we learned is that there is a large knowledge gap and an appetite for this information throughout the US Army and our allies. A few of the biggest lessons we learned from running the course were that:

We had to acknowledge we were creating something new.

The US Army has a long history of conducting urban warfare, from the Battle of Trenton to Aachen and from Hue to Fallujah and Mosul, but it has never committed sufficient training resources to fully prepare its large formations (battalion and above) to succeed in that environment. The frequency of urban conflict around the world has significantly increased over the decades since World War II. With over half the world’s population now in cities, urban has become the most likely and complex environment for military forces to conduct future missions across the range of operations: from high-intensity warfare against a variety of enemies to disaster responses around the world as climate change has increased the frequency and intensity of natural disasters.

There have been hundreds of urban warfare conferences, material experimentation campaigns, history writing projects, and tactical skills courses mainly focused on individuals shooting and breaching. But there has never been a formalized course for understanding and planning urban operations. This is true even after Congress put specific language in the 2020 National Defense Authorization Act to “establish an Army urban warfare center dedicated to the study and research of urbanization, mega-cities, urban warfare, and military operations in dense urban environments.”

With the first course of its kind, the 40th Infantry Division would be building the proverbial airplane in flight with no historical models to aid in the journey.

We would have to deal with a student population of various experience levels and familiarity with the topic.

The breadth of students’ experience was vast. The class consisted of mid- and senior-grade officers and noncommissioned officers, including logisticians, judge advocates, civil affairs practitioners, strategists, engineers, and even doctrine writers. There were representatives from several Army centers of excellence and many had multiple combat tours. But a majority of the students had no urban warfare experience. As the course progressed, most students either declared or wrote in AARs that they “had no idea how complex urban warfare was” or “felt completely unprepared” to deal with the difficulties of operating in urban terrain. Clearly the students realized that their professional military education up to that point had not fully prepared them for the complexity of urban operations, nor given them tools to succeed in this unforgiving environment.

We had to determine and stay focused on the overall learning objective.

The 40th infantry Division’s leadership decided that the Urban Planner Course’s outcome would be for participants to gain not only a much greater appreciation for the complexities of dense urban environments, but to learn operational approaches and capabilities, tactics, and techniques that the planners can use to succeed in these environments. The challenge for structuring the course was sequencing the enabling learning objectives for each lesson to maximum effect and eliminating subjects that did not resonate with the students or failed to accomplish the desired outcome. Gaining an appreciation of the complexity of urban warfare is good, but developing measurable skills to approach it is better.

What we were doing was about much more than a course or its students.

The planners’ course is just one of many lines of effort for the 40th Infantry Division with urban operations. The division’s leaders recognize that the Army does not have a dedicated unit, institution, or standard operating procedures (SOPs) that will help battalion through division staffs successfully plan, execute, and sustain operations in dense urban environments. Because of its unique position, based in a megacity, its alignment with US Indo-Pacific Command, and its proximity to the National Training Center, the division’s leadership believes that the division can become recognized experts and thought leaders in large-scale urban operations across the range of conflict and disaster.

The division command group wants to invigorate and engage the urban warfare community of interest via partnerships with academia as well as other DoD organizations and allies in order to drive the scholarship forward. They see several methods to do this, including advancing new concepts, publishing battle summaries, hosting urban wargames, and attending urban-operations-focused conferences. The division can become a test bed and feedback loop for the larger Army on urban capabilities, tactics, and techniques.

A key partnership for the division is with the nearby National Training Center, with the goal of forming an enduring urban warfare center for the Army. Eventually, the division would like to develop self-sustaining training infrastructure to perpetuate leadership and proponency in urban operations.

One of the lessons we learned is that we need to capture these urban-specific tactics, techniques, and procedures in a set of urban SOPs (what we’re calling “the Gray Book”), similar to the 101st Airborne Division’s SOP, called the “Gold Book.” In time, the Gray Book could become the central, organizing text for the urban planner course, much like the Ranger Handbook is to Ranger School.

The way ahead is not easy but the 40th Infantry Division’s leadership is committed to the future. The division plans to offer an improved course next time, leveraging the curriculum development skills of cadre like Dr. Jacob Stoil, an instructor at the Army’s School of Advanced Military Studies. The course designers will improve the read-ahead program to increase the starting point and baseline of students on day one, with historical and modern urban warfare case studies.

The course will also evolve to parallel the Army’s operations process in Army Doctrine Publication 5-0, The Operations Process—particularly intelligence preparation of the battlefield and course of action development—and will once again take place at the 40th Infantry Division headquarters in the Los Angeles metro area. Planners will first learn the larger strategic context of why the urban fight has been unavoidable and why large US formations need to get better at planning, executing, and sustaining operations in this uniquely complex environment. Then students will learn the many facets of the dense urban environment (including complex infrastructure, subterranean terrain, and the presence of civilians). The highlight of the course will be a deep dive into operational approaches and warfighting function capabilities, tactics, and techniques that the planners can use to overcome the urban challenge. The course will continue to include practical exercises like the visit to the National Training Center’s Razish training area, as well as the terrain walks through (or helicopter flight over) Los Angeles and its port complex and a culminating planning exercise.

In addition to a revised program of instruction, the 40th Infantry Division staff will continue to improve the Gray Book with urban-specific capabilities, tactics, and techniques with an eye toward seeking feedback from other units. The “Fighting Fortieth” is also looking for others to join the urban warfare community of interest who recognize the high priority of preparing the US Army and its allies for the future of armed conflict—urban warfare. Most importantly, we must continue to garner the support, resources, and prioritization for this endeavor. Urban warfare is the future and we must prepare.

Brigadier General Rob Wooldridge is the deputy commanding general (support) for the 40th Infantry Division, California National Guard. Brigadier General Wooldridge was commissioned as a field artillery officer in 1993, served on active duty for six years, and deployed to Kuwait in support of Operation Iraqi Freedom. He has previously served in multiple leadership positions within the California Army National Guard to include commander of 1st Battalion, 143rd Field Artillery; commander of the 100th Troop Command; and chief of staff for the 40th Infantry Division.

Colonel (CA) John Spencer is chair of urban warfare studies at the Modern War Institute, codirector of MWI’s Urban Warfare Project, and host of the Urban Warfare Project Podcast. He previously served as a fellow with the chief of staff of the Army’s Strategic Studies Group. He served twenty-five years on active duty as an infantry soldier, which included two combat tours in Iraq.

The views expressed are those of the authors and do not reflect the official position of the United States Military Academy, California National Guard, Department of the Army, or Department of Defense.

Image: Students at the urban planners course listen to a presentation by Steven B. Chesser, external affairs manager at Marine Exchange of Southern California (credit: Sgt. Simone Lara, US Army National Guard)

Today tech is a vast sensor that can connect with AI to determine the visitor to our town in registration GPS as location navigation as new come automatically to resend near immigration for those immigrants. War in urbanization challenges is terrorist which can be caused by anyone but is need to know exactly terror on-time action on surveillance immediately.

Is there not a fully instrumented MOUT facility at Ft Bragg? Why not rotate units through there?