This article is part of the National War College’s contribution to the series “Compete and Win: Envisioning a Competitive Strategy for the Twenty-First Century.” The series endeavors to present expert commentary on diverse issues surrounding US competitive strategy and irregular warfare with peer and near-peer competitors in the physical, cyber, and information spaces. The series is part of the Competition in Cyberspace Project (C2P), a joint initiative by the Army Cyber Institute and the Modern War Institute. Read all articles in the series here.

Special thanks to series editors Capt. Maggie Smith, PhD, C2P director, and Dr. Barnett S. Koven.

Good strategy is more than a collection of objective instrument packages, or a list of acceptable initiatives loosely bound to the pablum of fluffy objectives. Good strategy must have a clear, well-considered vision of the world combined with a uniting theory that focuses action on viable objectives and creates power and clarity amid uncertainty and complexity. Since the end of the Cold War, the United States has experienced a slide into strategic atrophy: we have slowly bled international support, squandered advantage, and burned resources while repeatedly coming out on the losing side of generally unnecessary conflicts. Our brief unipolar moment meant the immediate cost of this strategic atrophy was bearable, yet as we rapidly transition back to a period of multipolar competition, the likes of which hasn’t been seen since before World War II, that is no longer the case. It is time to begin putting our strategic house in order.

I have taught the art of security strategy at National War College for the last six years, and over that time my appreciation for the complexity of strategy and the value I put on the different elements of strategy has changed substantially. When I first started teaching, I delved deeply into the details of Art Lykke’s three-legged stool: ends, ways, and means. I focused most of my time and energy with students on developing viable ways-means packages and parsing the details of potential ends-means gaps. In other words, focusing on the mechanics of writing a strategy in the belief that good details meant good strategy. However, over the last few years, I have come to believe that, while a focus on the mechanics of combining ends, ways, and means remains valuable, it is less important than developing a crystal-clear diagnosis of the problem and then creating an understandable and viable theory of success. Fundamentally, I now believe the beating heart of good strategy is a clear, coherent, and well-challenged theory of success.

George Kennan is frequently referenced as a (if not the) preeminent post–World War II strategist practitioner. He is universally credited with the Cold War containment strategy and often with the Marshall Plan. Yet, upon further examination, Kennan created neither strategy. The actual containment strategy he suggested was never fully implemented and its recommendations were superseded by Paul Nitze’s NSC-68 less than two years after Kennan proposed them. Kennan’s ideas on European recovery also failed to evolve into what could even loosely be called a complete strategy. Kennan’s brilliance, and why he is justifiably America’s most revered strategist-practitioner, is rooted in how, for both the Cold War and European recovery, he clearly diagnosed the problem and developed an understandable and viable theory of success. Once that hard intellectual work had been done, the relatively easier work of creating and adapting strategies that accounted for the evolving international and domestic context could be accomplished by multiple individuals across the interagency. Despite repeated and substantial change to US national strategy between 1948 and 1991, Kennan’s theory of success remained the core. Kennan illuminated the corridor; others figured out how best to get through it.

Most basically, a theory of success (the term is agency dependent: while the State Department might seek a theory of success, the Defense Department’s focus will be on a theory of victory, USAID’s on a theory of change, and so on) is the strategist’s understanding of why, not how, a strategy will work. In other words, it is not an explanation of what actions will be taken, but instead a theory of why, and through what causal mechanisms, those actions will produce the desired end state. More specifically, it is a strategist’s hypothesis of expected causal relationships—namely, if we take X action, it will produce Y reaction/response from our target(s) because of reason Z, which will move conditions toward the strategy’s end state. This logic, explicit or implicit, underlies all strategic actions (i.e., ways). Consider the following example:

- Strategic Action: Sail a carrier strike group through the Taiwan Strait following significant Chinese People’s Liberation Army Air Force incursions into Taiwan’s air defense identification zone.

- Assumed Reaction: Beijing will recognize the strength of the US will to defend Taiwan.

- Theory of Success: China’s recognition of US resolve, demonstrated by sailing a carrier strike group through the Taiwan Strait, will make existing and future US deterrent threats more credible, thus improving the likelihood the United States’ preferred strategy of deterrence will work to prevent Chinese aggression against Taiwan and maintain the status quo.

Clearly, the above assumed reaction and resultant theory of success is only a hypothesis—it cannot be known for certain what reaction China will have. It is assumed China will see the action as a demonstration of will instead of an empty display. Additionally, it is assumed China will not take the opportunity to attack the carrier strike group. Furthermore, the strategist assumes this demonstration of US resolve increases the likelihood China understands any future threats to Taiwan will also be taken seriously by the United States. At a deeper level, the entire idea rests on the theory-based assumption that perceived will and perceived capability are the two elements needed for successful coercion.

By clarifying the expected results of strategic actions, the causal mechanism believed to lead to those results, and how those results are expected to move the context toward the desired end state, the strategist brings greater analysis to bear on often unchallenged or unrecognized assumptions, biases, and gaps in knowledge. This focuses attention on key questions: When have similar actions (ways) in the past produced an end state or condition like what we are shooting for in this situation? When have they failed? Why did they fail? How can we avoid similar failure? It also facilitates the identification of cognitive biases, like mirror imaging, availability, or illusion of control, by forcing strategists to make explicit their expectations. The process also prompts additional questions like Alexander’s Question: What information, if I had it, would make me change my mind? In the example of sailing a carrier strike group through the Taiwan Strait, we might ask, Since we have done this before, what response did we previously see from China? Is that the same response we are expecting this time? Why or why not? Or, In what other ways might China respond to this action, and what information would lead us to believe one of those responses is more likely than our expected response? In short, an explicit, clear, and understandable theory of success facilitates a much deeper exploration of a proposed strategy, which creates more opportunities to identify risks to, or from, the strategy before they come to fruition.

Strategic actions are initiated because of the hypothesis made in the theory of success (and its assumptions). Said another way, a strategist’s theory of success drives strategic choices—completely, whether the strategist knows it or not. A good theory of success is based on clear analysis of context paired with a uniting model to interpret the results. There are many approaches available, but in the current context, the competitive strategy framework provides a valuable option. This framework prescribes engaging in a disciplined process of net assessment of competitors, other relevant international actors, and internal, domestic conditions. The process further requires the identification of strengths, weaknesses, and durable propensities. Using the Kennan example, his theory of success was based on assessments of the nature of military power and an evaluation of which states or regions around the world could generate strategically significant military capabilities, which led to his containment hypothesis. But his conceptualization of successful containment was also grounded in an assessment of the long-term health of the domestic systems and proclivities of the two major competitors—the United States and the Soviet Union. Kennan’s analysis gave him confidence: if the West could maintain control of key regions around the globe and avoid being either attacked or undermined it would, in the long run, prevail. The problem is, unlike Kennan, many strategists and policymakers do not clearly understand what their own theories of success are, or they fail to define them. Even when strategists and policymakers both understand and define their theories, they often fail to take the next step of identifying and challenging the assumptions upon which their theories of success are built. The result of failing to identify, define, and validate the theory of success is a strategy that is “nothing more than a loose collection of initiatives and misplaced hope.” The implications of such incoherent strategy for strategic competition are clear.

First, using military language, a theory of success, when clear, explicit, and well considered, is the strategic version of commander’s intent. It provides subordinate or lateral actors and institutions a strategy heuristic, allowing them to make decisions about the development of their own innovative, timely, and tailored responses to the evolving context. Simultaneously, a theory of success helps limit the play of operational and strategic creativity to the logic path set forth in the founding strategy, which facilitates rapid, tailored responses and iterative evolution of strategy while reducing the likelihood of line-of-effort or iteration fratricide. In this context, John Boyd’s OODA loop is as relevant to the strategist-practitioner and policymaker as it remains to the fighter pilot. If US strategic choices are made more rapidly, by those lateral or subordinate elements that have a clearer and more immediate view of the changing strategic context, then the United States will be able to cumulatively outthink our more hierarchical, top-driven strategic competitors by getting inside their strategic OODA loops. In concept, the Joint Chiefs of Staff have explicitly emphasized getting in the adversary’s OODA loop by highlighting the importance of “intellectual overmatch.” However, without a flattening of the strategy decision structure, something that could be facilitated by a clear theory of success, intellectual overmatch buys limited strategic benefit.

Second, a theory of success clarifies the underlying hypothesis and supporting assumptions of a strategy. This gives US intelligence agencies, the policy community, think tanks, and scholars a defined set of targets from which they can develop valuable intelligence requirements and conduct analysis. If a nation’s entire theory of success or strategic hypothesis is underpinned by three or four major assumptions, then proving or disproving those assumptions (e.g., looking for trends and indicators of accuracy or inaccuracy) is a clear and exceptionally beneficial process for the national security community to undertake. Pitting the combined analytic power of our intelligence agencies, the broader policy community, and the think tank and academic communities against a set of underlying assumptions based on a clear theory of success substantially decreases the chances of the United States charging boldly and unswervingly down the wrong strategic path. In fact, the ability to leverage vibrant and robust governmental and civilian analysis and public debate is an asymmetric advantage of our liberal society—an advantage that is best leveraged when a theory of success is clearly defined.

I often tell my students that everyone who writes a strategy or engages in developing a strategy has a theory of success—however, most do not actually know what that theory is. The theory is assumed, felt, believed, or held in the subconscious but nonetheless guiding strategy development. The theory of success needs to be overt, direct, understood, analyzed, challenged, and then promulgated as the most important element of the strategy for a reader or implementer to take away. Because, when all the details of a strategy are stripped away, at its core a strategy is a theory of success. George Kennan gave the West a theory of success for the Cold War. That theory carried the United States and our allies, in admittedly halting, indirect, and frequently stumbling steps, to victory. The United States has yet to identify a theory of success to carry forward in its strategic competition with China and a reemergent Russia. Without one, our strategy and policy will continue to be inconsistent, incoherent, and frequently self-conflicting.

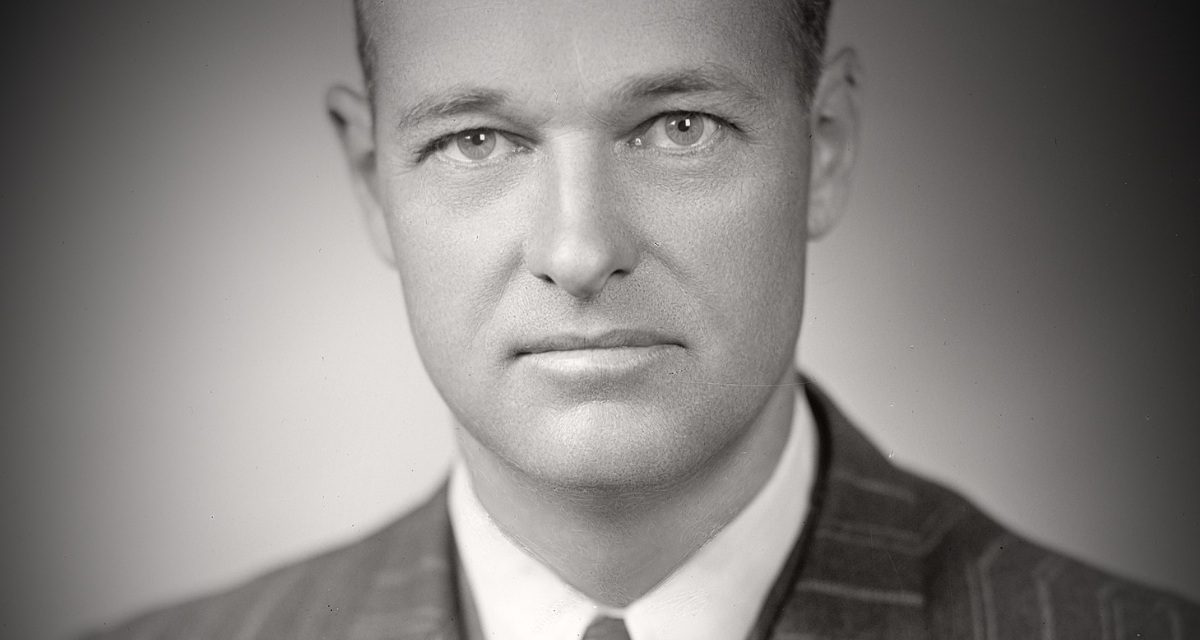

Colonel Steve Heffington is a professor of national security strategy at the National War College, where he has been a faculty member since 2015. While at NWC, Colonel Heffington has served as a deputy core course director and director of education technology, and has been the NWC Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Professor of Military Studies Chair since 2017. Colonel Heffington is the coauthor of A National Security Strategy Primer.

The views expressed are those of the author and do not reflect the official position of the United States Military Academy, Department of the Army, or Department of Defense, or that of any organization the author is affiliated with, including the National War College, National Defense University, and US government.

And I suspect George Kennan would have preferred of a more conservative, cautious, careful definition of success instead of trying to impose our will, especially when in the relatively much less powerful position we are now.

I've read he was in our embassy in Moscow at or after the end of the war, like a then young Martha Mautner nee Hallaran was.

In my younger days, I thought containment was too passive, but Kennan was obviously right.

In 1986, I believe it was, Martha Mautner came up to Juneau to speak at the Juneau World Affairs Council – Judge Thomas B. Stewart was its guiding light, and it is incredible the major figures he got to come to Juneau and talk to us.

Before her talk, I met her husband Karl who was German and said he was a paratrooper in the Battle of the Bulge, whereupon in my barely high school German I asked "Und welchen fallschirmjaeger division waren Sie in, Herr Mautner," whereupon he answered in wry but accented English, "the 82nd Airborne."

Karl was a major factor in West Germany's economic recovery and democratic blossoming.

Anyway, after her talk, I think I persuaded Martha that the 1940 Katyn (and other) Massacre(s) was the Silver Bullet truth issue that could bring down the Soviet regime (as it did, rallying the Poles especially – it wasn't just economics. The Russians themselves were sick of the lies and looked to us in the West to help them escape those. But then we instead ….)

But I'll never forget Martha then asking, if not demanding, regarding the Soviet regime's fall, "What then??" which dumbfounded me … wasn't that what we wanted? … but after what has happened to the Russians people since … what our neocon economic and foreign/military policies have done to them as well as others … I have sadly understood her point.

To her credit, she deeply cared about the Russian people … as I suspect George Kennan did too.

Martha was a and possible the key kremlinologist at the time, and we then started aggressively making Katyn an issue, which was in a sense crossing the containment line.

And regarding the current Ukraine crisis of our making, Vox has a 27 January 2022 article by Jonathan Guyer which featured this fact: "Members of the alliance didn’t always foresee its expansion and, three decades ago, some of America’s most renowned foreign policy thinkers argued that NATO should be nowhere near Ukraine."

And they included George Kennan.

Something in Col. Heffington's article I notice was his defense of free discussion even entailing disagreement on strategic issues. Meanwhile, the Biden Department of Homeland Security has just issued its 7 February 2022 bulletin warning that distrust in government – and disagreeing with it? – has the potential to be exploited by domestic terrorists for mass violence and such distrust in the social (and other, presumably) media is to be monitored … until 22 June 2022(?).

This blithely overlooks that distrust in government was the very reason for our written Constitution for our representative democracy – our democratic republic – and that that such distrust is politically healthy and indeed patriotic.

Note the rightful concern that former West Point Combating Terrorism Center (CTC) employee Arie Perliger caused when he wrote that anti-federalists “espouse strong convictions regarding the federal government, believing it to be corrupt and tyrannical, with a natural tendency to intrude on individuals’ civil and constitutional rights. Finally, they support civil activism, individual freedoms, and self government. …." (Washington Times, Rowan Scarborough, 21 January 2013.)

From the center of the third paragraph of our article above:

"Kennan’s brilliance, and why he is justifiably America’s most revered strategist-practitioner, is rooted in how, for both the Cold War and European recovery, he clearly diagnosed the problem and developed an understandable and viable theory of success."

If we were to define "the problem," in the post-Cold War, as (a) traditional social values, beliefs and institutions (b) standing in the way of states and societies (to include our own states and societies ) becoming better able to interact with, better able to provide for and better able to benefit from such things as capitalism, globalization and the global economy. (Herein, our belief being that — if states and societies were to come to exclusively "worship" and to exclusively depend upon capitalism, globalization and the global economy — then amazing prosperity would make conflict between states and societies less likely?),

Then, from that such "problem" perspective, what would an understandable and viable "theory of success" look like?

Great to read Kennan is getting the recognition he deserves and the furture of American strategy is being taught in this way. My thesis 'Shadows of Arlington' examies Kennan and his influence through strategic theory. Understanding the importance of how others view the world, to enable success in politics is so important and often overlooked in Grand Strategy theories.

Charlotte Fenton PhD candidate at University of Hull UK.