During dinner at my house one night, not long ago, the conversation between my two daughters (thirteen and eight years old) and me and my wife (both Army veterans) turned comical:

Daughter #1: “Dad, all you did in Iraq and Afghanistan was play Call of Duty.”

Me: “Well, I mean, that’s not ALL I did over there.” (…yes it was)

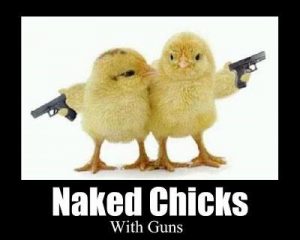

Wife: “Yeah, he also spent a lot of time looking at pictures of naked chicks with guns.”

Wife and me: (both laugh at the inside joke)

Daughter #1: ”Daaaaadddd!!!”

Me: (teasing) “What? I was deployed. That’s what happens when you’re deployed.”

Wife: (teasing) “Want to see Daddy’s ‘naked chicks with guns?’”

Daughter #1: (horrified) “No way! I’m sure I’d be totally scandalized!”

Wife: “You want to see this.”

Daughter #1: ”No I don’t!”

(^this goes back and forth several times between Wife and Daughter #1)

Daughter #2: (has no idea what’s going on right now) “I want to see!”

Me: (pulls out phone, shows daughters the picture of “naked chicks with guns”)

Daughter #1: (totally scandalized) “My childhood is ruined.”

Daughter #2: “Awwwww they’re so cuuuute!!” (voice drops two octaves) “…and DEADLY.”

I deployed to Afghanistan a total of four times between 2005 and 2009. My last tour was with the national-level Joint Special Operations Task Force, but the first three were with the 160th Special Operations Aviation Regiment, AKA the “Night Stalkers.” As the battalion intelligence officer (S2) for 2nd Battalion of the 160th, while in Afghanistan I was dual-hatted as the J2 for the SOF rotary-wing task force. This organization I’ll call “Task Force U.P.S.” because, among other reasons, as far as I know no such unit designation ever existed. What being the J2 meant in practice was that my team and I gave the pilots and air crews of the Task Force as much information as we could about the weather (mostly handled by the Air Force weather team), terrain, flight routes, and enemy activity in support of their mission to be “on time, on target, plus or minus thirty seconds.”

Our Task Force consisted mainly of the heavy-lift MH-47G variant of the Chinook helicopter. These were the largest, and fastest, helicopters in the Task Force’s inventory. They were also the airframes that were best suited to operate in the high altitudes and thin air that comprised much of the parts of Afghanistan where we operated.

I came to the 160th after being “across the airfield” with the 5th Special Forces Group, an organization that treated me extremely well. One of the many things that I liked about the 160th was that even as an enabler or “support guy,” I actually had to try out for, and be accepted by, the 160th. In contrast, my assignment to 5th Group was a “needs of the Army” gig, so my coworkers on the support side were “needs of the Army” quality: some very good, some not so good. There was no trying out for a job like mine in Special Forces, something which over time, and despite my affection for the unit, I came to view as an unmitigated failing with very serious negative consequences.

Because it was so competitive to get into, and competitive to stay in, the support side of the house in the 160th operated at a much, much higher level of quality than anything I experienced previously. Additionally, the fact that an assessment and selection program existed for support troops meant that the pilots I supported knew that I, like they, had to try out for and be selected by the unit. The fact that I also had to do Green Platoon, the initial training block all Night Stalkers are expected to attend, afforded me the opportunity to establish credibility and relationships with some of the pilots before I was even officially a member of the unit. This paid off huge during deployments. Three of the things that I remember most about my time with Task Force U.P.S. were competition, Call of Duty, and “naked chicks with guns.” These three very different things, and the way they contributed to the 160th’s unique culture, are explained in detail below.

Competition

The motto of the 160th is “Night Stalkers Don’t Quit.” My experience was they totally live up to that mantra. One thing you need to know about the 160th is that everyone in it is extremely competitive. About everything. It doesn’t matter what it is; if it can at all be turned into a competition, it will be, and IT IS ON. In Afghanistan members of the Task Force would compete to see who could do the most pushups, who could lift the most in the gym, who could do the fasted two-mile on the treadmill. There were competitions to see who could hold their breath the longest, who could name the most states and state capitols, just about anything. And these were just the competitions outside of the cockpit. Basically, if it was a “thing,” someone would make a competition out of it. And if it was a competition, then everyone in the Task Force wanted to win.

For example, on my first deployment to Afghanistan as J2 for Task Force U.P.S., I installed a pullup bar in the door jamb of our plywood workspace (known as a SCIF, a Secure Compartmentalized Information Facility). On the white board outside of the SCIF, I blocked off a spot where we posted names and number of pullups completed by the members of the J2 section. Pretty soon, some of the pilots noticed this and were adding their own names and scores. This then immediately turned into a competition, with everyone trying to outdo each other. In short order, we had to have different categories: male and female max scores, pilot vs. support max scores, and longest time to maintain one’s chin over the bar. We eventually even had people from other units come over to try their luck. Since the leader boards were erased every week, and there was a constant flow of personnel in and out of theater, there were always people who wanted to come and compete. I think the most I ever saw anyone do was forty-two. At that time I could only do about ten. The only time my name ever got to the top of the leader board was if I did my pullups immediately after the board got cleared of the previous week’s scores . . . and even then, it didn’t say up for long.

One time someone got a yo-yo in a care package from home. In no time, yo-yos started appearing all over the JOC, with competitions over who could do the most tricks, and who could yo-yo for the longest period of time. I hadn’t held a yo-yo in years, but since it was a competition, I got in on the act too. Then there was the juggling. One time, a pilot walked through the JOC juggling four balls. He didn’t say a word; he didn’t need to. Just the fact that he could do it, and the other Task Force members couldn’t, meant that IT WAS ON. Almost immediately, people were looking up “how to juggle” on the Internet and practicing with whatever objects happened to be handy. I think this lasted until the operations sergeant major, tired of mis-tossed balls bouncing all over his workspace, summarily banned them from JOC. Juggling was one area where I flat-out had to admit defeat; I never did gain any competency at juggling.

I was, however, pretty decent at playing guitar. If I turned it just right, I could squeeze my Martin Backpacker guitar (and its soft case) diagonally across the top of my Tuff Box and take it with me on deployments. I installed two wood screws into the plywood wall of the SCIF and suspended the guitar from its tuning screws. Sometimes visitors to the SCIF would come visit and play it for a while, and I’d take it down and play it from time to time during lulls in the missions. I made it a practice to leave the door to the SCIF open to the JOC floor unless we were doing something particularly sensitive inside the SCIF (which was almost never), but I’d usually shut the door when I played so it didn’t bother anyone on the JOC floor. One day the J3 mentioned that he liked to listen so I left the door open from then on. A couple of pilots and staff members, including one of my own analysts, learned to play guitar while in Afghanistan. They ordered some of those super cheap mini-guitars for kids from Amazon or Wal-Mart and had them shipped over. “If the S2 can do it, I can do it too.” Competition.

The pilots’ competitive nature was evidenced on operations as well. Everyone wanted to be the best at everything, and when it came to providing rotary-wing support they definitely were. Importantly, however, they also realized the limits of their capabilities and adjusted accordingly. For example, while everyone aspired to be a Flight Lead, the highest level of qualification within the Task Force, not everyone was able to meet the requirements. Additionally, it might simply not be a specific pilot’s role to be a Flight Lead; a field-grade officer’s job might be to command the mission, not serve as a Flight Lead. That still didn’t mean everyone didn’t want to be the best, at everything, all the time. That sentiment is not unique to the Task Force or even to SOF, but I saw its clearest manifestation, and the benefits of it, while I was in the 160th.

Call of Duty

While the members of the Task Force would compete over anything, the hands-down most competitive thing we ever did together outside of combat operations was to play Call of Duty. Today, Call of Duty is a household name and gaming giant, but we were in on the ground level of the first edition of CoD. Prior to my first deployment with the Task Force the only first-person shooter game I had ever played was the original Doom. One day I was minding my own business in the SCIF after helping support an uneventful mission, when a couple of pilots came in and, more insisting than inviting, asked us to play. I declined at first, mostly because I didn’t want to get “owned” in a game I never played before, but also because I knew that playing games on our laptops ate up bandwidth and slowed down the system.

But that is where our battalion signal officer, the S6, really came through for us. While not a gamer himself, he realized how important Call of Duty was to the morale and esprit de corps of the Task Force, so he created a LAN system internal to our building through which we could network our laptops and play CoD without degrading the overall network. We simply unplugged a red cord, inserted the green one, and IT WAS ON.

Predictably, we got our asses handed to us the first time we played. To begin with, the pilots wanted to play “pilots vs. support guys” (a standard team delineation, we found). There were far more pilots than support guys playing Call of Duty, so the pilots had a numerical advantage. Because the game “auto-balanced” teams, the pilots simply shifted their “good” players onto the pilots’ teams, and the scrubs onto ours. More importantly, because they had played the game—a lot—and none of us had ever played before, they had an experience advantage. And because of the fact that they had played together several times, they had an organizational advantage.

Losing was bad enough, but after a few games, when we stopped playing out of frustration, the pilots came down to taunt us. After getting crushed in the first set of games we played, I had little interest in continuing. However, the pilots’ unceasing agitation and everyone’s natural competitiveness drove us to continue.

So, we did what intel guys do: We strategized. We organized. We war gamed. We looked up strategies (and cheat codes, although we never used them) online. We figured out how to use our microphone-equipped headsets to talk to each other while we played. We “pulled imagery” and conducted Intelligence Preparation of the Battlefield (IPB). Most importantly, we practiced.

And we got really, really good.As it turned out, Donny, our imagery analyst, was hands down the best CoD player in the Task Force. Unlike the rest of us, he had grown up with first-person shooter games and was a true master.

While he infinitely preferred playing Halo on his Xbox to playing CoD on the computer, the skills were transferrable enough that he quickly adapted to the differences in both the game and the controls, and was soon the master of all he surveyed. It also helped that he was able to use the enormous, hi-definition flatscreen TV we had in the SCIF to show imagery products, instead of a low-resolution laptop screen like the rest of us. He also had a government-purchased, souped-up Alienware computer system designed to speed up imagery processing time. Although I didn’t entirely understand the technological nuts and bolts, Donny explained that the system gave him a split-second advantage in computing power which sometimes made a difference during game play.

Over time, the “support side” got so good as a team that we could handle a numerical disadvantage. We knew the ins and outs of the various game scenarios so well, and worked together so well as a team, that we started dominating the competitions.

And the pilots would get ANGRY.

It’s possible to communicate via text during the game, either team-internal or to everyone playing. When we first started playing, the game-wide messages were usually taunts from the pilots directed at us. Over time though, especially when we started dominating the competition, the frustration started seeping out. Our building was made out of plywood, and the pilots would stomp their feet on the floor above us to show their displeasure during games. It made me smile.

To further stir the pot, and largely for our own amusement, we started sending “intel reports” to the pilots into which we inserted staged shots of CoD scenes. The first time I sent one out, I followed the format of the regular, classified updates I would send them, and mixed it in with the regular reporting. Of course the pilots discovered the fake report immediately, and good-naturedly made a big production out of the “false reporting.” They retaliated with fake CoD-related “RFIs” (intelligence Requests for Information), which we would then have to answer.

Call of Duty wasn’t merely a game. It was an important part of the organizational fabric, something that brought us all back together after a mission, something that allowed us to decompress, and helped reinforce team dynamics. It would have been possible, and totally fine, for me to shut the door to the SCIF and only come out when I needed to talk to the pilots about an upcoming mission. But then, that wouldn’t be the 160th.

I know it’s easy for people to read what I just wrote and think, like my daughter did, “Must be nice—all these guys did was sit around and play video games all day long.” That’s not the case at all. Of course life in Task Force U.P.S. wasn’t all downtime and Call of Duty, but I’m not going to talk about those “other” missions, the stuff we were really there for. Suffice it to say that there was plenty of action going on when it was “action time.” Those who have the clearance to hear those stories already know them. Those who don’t have clearance, you’re never going to hear them from me.

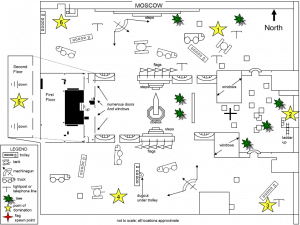

While both my ability and desire to comment on the operational side of what we did downrange is very limited, there are a couple of things I can share. On the front wall of our SCIF was a gigantic flat-panel television, through which we could watch live feeds from any number of operational or intelligence channels. The main thing we used it for was to which live surveillance footage, which mostly came from Predator unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs). On my desk, I had three laptop computers: one for Top Secret information, one for Secret, and one that was Unclassified. Our S6 had wired up the computers and the satellite radios in such a way that with a click of a mouse button I could talk to our pilots in the air, in real time.

One of my responsibilities as J2, and my only “active” responsibilities during actual missions, was to monitor the aerial surveillance feeds overwatching our helicopter landing zones (HLZs) and relay any important information to our pilots. My battalion also had me call the mission commander one minute out from the HLZ to give a final status of the landing area.

Now, this is the 160th. They have a job to do, and they are going to do it. They are going to deliver their package “on time, on target, plus or minus thirty seconds,” no matter what I tell them on the radio. If a landing was going to be aborted, it was going to be because of something a pilot or crew chief saw or said, it wasn’t going to because the J2 back at the JOC got nervous about something he viewed on a Pred feed from the safety of the forward operating base. I suspected that part of the reason they asked me to make those calls to them was more for my benefit than theirs; it was their way of allowing me to feel part of the mission. But it was also indicative of a culture of developed trust. I asked one of my friends about the calls one day, and the conversation went something like this:

“So, those one-minute-out calls I make for you every mission. Generally speaking, no matter what I tell you, you’re going to land there anyway, right?”

“Right.”

“So, why do you have me do it?”

“Well, with the brownout we can’t see very well on the LZs, and we know you and trust you, so it makes us feel good to know that you have eyes on when we’re going in.”

It made me feel good, too. That kind of trust is hard-earned.

I remember during one deployment, in the winter, the weather was so terrible that all of our operations were grounded. We had a mission scheduled to support the Australian special operations forces, a rather complicated one that involved a high-risk infiltration movement after an offset helo insertion. I prepared my portion of the Air Mission Brief (AMB) . . . and the mission got postponed due to weather. Most of the time, our missions were short-notice and my contribution to the AMB was a bare-bones PowerPoint affair with minimal images and text. But having no other mission support requirements, and nothing but time on my hands, I decided to continue to “improve” my portion of the briefing. I pulled updated imagery, did deeper research into the target and the surrounding area—and started adding PowerPoint features.

The standard for our briefings was “no bells and whistles.” Fancy transitions, animations, and graphics were time-consuming to make and had a tendency to distract from the important information on the slides. But when the mission got rolled for a second day, I decided (mostly for my own amusement) to go all out on this particular briefing.

By the time I was done I used just about every feature PowerPoint had. I embedded video. I animated graphics. Icons that would normally be static during the briefing now took on a life of their own. MH-47 helicopters appeared to fly in from off screen, disgorge their cargo, and fly away. “Tracer fire” emanated from suspected enemy positions, until they were blasted by the AC-130 that circled ominously overhead. Heck, I even had a soundtrack. And I still managed to fit it all into the time period allocated for the S2’s portion of the Air Mission Brief. The best part was, since I had days to work on a briefing for which in normal circumstances I’d have an hour or two at most, I was able to rehearse to the point where the slides were set on a timer to “build” automatically while I briefed.

There was no particular need to do any of this; other than a “PowerPoint Ranger” skill showcase, the additional work didn’t add much value. I just wanted to see how good a job I could do when I had that much extra time. And besides, there is only so much Call of Duty one can play in any given day.

When, after three days, the weather cleared up enough for us to actually do the mission, we were finally able to do the brief. The Aussie special mission unit commander and his team filed in, as did our regular team of pilots and support personnel. I was initially worried that the extra material might be distracting, or worse yet not work properly, but fortunately, it went flawlessly. When the first animations started, there were some over-exaggerated “oohs” and “ahhhs” from the pilots, one of whom joked, “Now he’s just showing off.” Which, if I were to be honest, was true. And it’s better than saying, “The S2 was really, really bored the last three days.”

While the slideshow progressed automatically behind me, I talked through the weather, the route, and enemy actions. This was, perhaps, the most detailed and most complicated (and, let’s face it, most needlessly complicated) three-minute briefing I’ve given in my entire life. For the members of our Task Force, this briefing was a one-off. I never did anything like this briefing before or after. But to the Aussies, who had never worked with us before, this briefing was “business as usual” for us as far as they were concerned. After the briefing was complete, I heard the Aussie mission commander ask his S2, “Patcho,” why he didn’t do briefings like that. I felt bad for a moment until I realized he was kidding. (Patcho and I ultimately became friends; we played guitar together a couple of times in between missions, and he hosted me at 2 Commando during my visit to Australia. A few years later I was able to reciprocate by hosting him at my house in Northern Virginia for a Super Bowl watching party. We ran into each other again in New York City at a big party Google was putting on for veterans. We worked with a lot of Coalition partners in Afghanistan, but as a group I think the Aussies were my favorite.)

While the briefing went well, that mission itself did not. There were no issues with the offset insertion, but the Aussie ground force was compromised during infiltration (a common occurrence for any strike force in these kinds of high-risk missions) and a running gun battle ensued. The pilots called back with the coordinates that the ground force had requested as the extraction point, and Donny pulled up the imagery of the area to scrutinize it for suitability. While he worked the Alienware gaming laptop (now fulfilling its legitimate purpose), I directed the Predator camera to zoom in on the proposed landing site. Even with the high-quality camera, it was still night, and it was hard to tell if there were flight hazards in the rocky terrain.

Standing in front of the giant plasma TV, now showing a very real life-or-death struggle instead of Call of Duty shenanigans, Donny and I had a quick conversation. “I think they can land there, but they need to know that it’s a pinnacle landing and it’s going to be a little rocky,” he said. “If they can give me two more minutes I can probably find a cleaner PZ.” I quickly looked over his planning figures and at the Pred feed. I concurred with his assessment.

“Roger.”

I pressed the button to key my satellite connection. “Atlas 2-3 (I’m making up this callsign), this is Blackhorse 2. Donny says he thinks you guys can land there, BREAK,” I said, releasing the “talk” button and giving the radio proword to indicate a continuation of the message, which would have been, “but, we need a little more time to be sure.” I say those words “would have been” because I never had time to get the rest of that thought out, since as soon as I unkeyed the microphone at the “BREAK,” the small form of an MH-47, shown white on the Predator’s thermal display, came barreling in from the right side of the screen. The pilots heard me, whom they trusted, say that Donny, whom they also trusted, thought they were good to go. And with that, IT WAS ON.

Saying anything else at this point would have been a distraction to the pilots, so I said nothing, and watched with a sense of thrilled apprehension. Was Donny right? Should I have tried to wave them off? What’s going to happen now? On the screen, we watched as the MH approached the mountaintop, whipped around 180 degrees, and dropped the ramp, and as a handful of small figures, white in the infrared view, ran up the ramp and into the bird. And then they were all gone. It was the kind of extremely complex maneuver that the pilots regularly made look easy. Nonetheless, all of us in the SCIF felt pretty tense until the helicopter lifted back off and flew off into the night.

“Well Donny, I guess you were right.”

“Roger, sir.”

“Good job.”

“Roger, sir.”

Our relief was palpable

We found out later that there was some minor damage to the ramp from the pinnacle landing, but no one was hurt and the aircraft was still fully mission capable. Another successful mission for the Night Stalkers.

That was the point when I realized how competition made all of us better. The drive to be the best at everything helped these Night Stalker pilots be the best helicopter pilots in the world. Our teambuilding activities, whether it be during assessment and selection, or Green Platoon, or in unit-level soccer matches, or through Call of Duty, engendered the kind of trust that made it okay to risk lives and millions of dollars of equipment on the say-so of a group of people miles away from the action. Those pilots were waiting for the green light from us and when it came on, they went for it. They didn’t need my “but.” There was no time for “but.” “But” causes hesitation. Hesitation gets people killed. I never considered a “but” during a mission ever again.

Naked Chicks With Guns

Every Sunday afternoon, operational requirements allowing, our battalion commander would take all of the officers “out to dinner.” This involved us loading up in our vehicles, usually Toyota pickup trucks and Bongo vans, and making the short drive down the airfield to the Air Force dining facility for dinner meal, which, given our offset mission cycle, was actually lunch for us. This was a rare opportunity for the officers in the unit to get together all at once (our various roles and operational cycles meant we were rarely all in the same place at the same time), decompress, and share important information with each other. Sometimes after lunch we would stop off at the Green Beans on the way back to the Plywood Palace and get a coffee to go. It was a rare moment of downtime in an otherwise very “eventful” work environment.

After this lunch, there would be a battalion-wide information meeting in the briefing room of our two-story plywood building. At this meeting, all of the staff sections would update the entire Task Force on important information related to their specific section: the S3 would brief pending operations, the S1 would talk about pay and personnel issues, the S4 would talk about supply, and so on. Most of the briefings were pretty basic, but I remember the chaplain in particular was a great public speaker, to whom the commander usually gave the final word at these meetings, and who would deliver rousing non-denominational benedictions to these meetings.

Unlike the daily mission briefs that took place in a small room in the back of the first floor of our building, these weekly updates took place in the large second-story briefing room. This room was arranged with stadium seating, which allowed everyone to see what was happening in the front of the room. There was always a sense of excitement at these briefings, which not only served to keep the Task Force informed but also helped make sure they kept personally connected with each other. The briefings were part information and part entertainment, and humor played a big part in the briefs.

One thing that was always a crowd pleaser was footage of operations. I was usually able to get the combat camera footage off of the classified server, and get the gunship footage directly from the AC-130 team. Our battalion had a strictly support mission, so it was useful for our Task Force to see the fruits of their labors in the footage taken from the ground forces’ helmet cameras and the overhead surveillance footage.

I think it was Molly, our intel analyst, that figured out how to sync rock music to gunship video through the use of Microsoft MovieMaker. The first time we showed footage with an actual soundtrack, it was a huge hit. Unfortunately, it created the expectation that we would have something similar every week. I found out that the term for this type of footage was “Predator pornography,” or “Pred porn” for short, which included any type of combat footage whether it was from a Predator or some other source.

One week, the weather was so bad that almost all operations were halted. Most of the operations that did occur were reconnaissance and surveillance, which tends to be . . . well, pretty damn boring to most people. There was no Pred porn! What to do? My fellow Task Force members had been conditioned to expect “bread and circuses” from the S2 shop at the weekly update briefs, and I knew that they would express deep displeasure if they were deprived. Fortunately I knew there was at least one thing that Task Force U.P.S. liked more than watching Pred porn. So I went to the Internet and searched for “naked chicks with guns.” Finding something I felt was appropriate, I inserted it into my briefing.

Sunday finally came, and there was still no suitable war footage to show. When I finished the “official” portion of my briefing, I took a deep breath and announced, “I’m sorry folks, but due to the weather, there is no Pred porn today—.” As expected, the reaction was immediate. No sooner had those words left my mouth than cat-calls and empty water bottles tossed in our direction conveyed the deep displeasure felt by the audience.

“Booooo!”

“S2, you SUCK!”

“You had ONE JOB!”

“Get a rope!”

After the initial good-natured tumult died down, I was able to finish my sentence. Raising my hand, and keeping a wary eye out for additional projectiles, I started again. “There is no Pred porn today, BUT I do have something I think you all will like: naked chicks with guns!”

The assembled audience roared its approval.

“Yay S2!”

“Finally, something useful from the S2 shop!”

“You won’t do it!”

I glanced at my battalion commander before I proceeded. He eyed me suspiciously but said nothing; another indication of trust. He knew that I knew that showing Pred porn at a Sunday briefing in front of the entire Task Force U.P.S. was one thing; showing actual porn would be something else entirely. I’d never show pornography and he knew it. He trusted me enough to let the situation develop.

After a pause for dramatic effect, I pressed a button to advance the slide, which depicted . . . two fuzzy yellow baby chickens onto which someone had Photoshopped tiny handguns. After a moment to process that they were seeing literal “naked chicks with guns” and not what most of them probably expected, the audience burst out with laughter and the briefing was saved.

While I spent almost all of my deployments supporting operations from the safety of my desk, I did fly one or two missions during my time in Task Force U.P.S. The MH47 has a third “jump seat” between and slightly behind the seats for the pilots. Most of the time that seat was empty on missions and the pilots often invited us members of the J2 section to go on missions with them. These were usually the “low-risk” missions where having a third wheel on board wouldn’t adversely affect the night’s operation. I rarely went on missions, as I had the attitude that I couldn’t do my job in support of the mission, if I was on the mission.

But, as I’ve mentioned before in earlier writing, I knew that there were only so many times that I could turn down the offers before the pilots would start to think I was scared. Credibility being everything for an intelligence officer, I couldn’t allow that to happen. Besides, going on missions was fun. So every once in a while I’d get to kit up and go on a flight. But I didn’t do it often. During one protracted mission we even got to fly a bit in the daytime, a rarity for us Night Stalkers. While most of what I saw of Afghanistan was either barren or filthy, there are some portions that are quite beautiful. It’s a shame that such a country, and more importantly its people, have been wracked by so much war for so long.

As a military intelligence officer, an enabler, a support guy, whatever you want to call me, I felt connected to, accepted by, and valued by the 160th in a way I had never felt before. Part of it was the nature of being in a unit where everyone, including the support troops, had to try out to be in the unit in the first place. Part of it was the nature of being in an aviation unit, where the supported elements (pilots) knew that they absolutely couldn’t do their jobs without the support side of the house. This was in stark contrast to infantry and even Special Forces units I had served in previously, where the prevailing attitude was often, “I don’t need support, I can do everything myself.”

Part of the difference between the units was the fact that technology had progressed to the point where I had access to intelligence resources and communications technologies that enabled me to make a genuine contribution to the planning for and execution of our missions. Part of it was unsurpassed (in my experience) level of commitment, teamwork, competitiveness, and unit esprit. But perhaps the final, and certainly most important thing was that the 160th was just chock full of genuinely good people. That aspect was what made the 160th a hard unit to leave when I attained the rank of major and got promoted out of my job. I had to find another job somewhere, so I made some phone calls and landed an assignment at the “big” Task Force level, “Task Force Purple.”

But that is a story for another time.

Charles Faint is an active duty US Army officer assigned to the United States Military Academy at West Point, where he currently serves as the Course Director for MX400, the Superintendent’s Capstone Course on Officership. This personal vignette from his service in Afghanistan does not reflect an official position of the 160th Special Operations Aviation Regiment or the United States Military Academy at West Point. As part of the pre-publication clearance procedures, all names, call signs, and task force names were changed to fictitious ones. Sorry, “Donny” and “Molly.”

Absolutely one of the best accounts of the Nightstalker ethos I have ever read. It's uncommon to read an author that really grasps the synergistic effects of trust and competence. Even more so one who is so "comfortable in their niche" and not prisoner to the frailties of ego and vanity.

Thanks for pulling the curtain back in such an entertaining way.

Shape the young officers in your charge. They will do well to learn your ways.

NSDQ