During her year as a student at the Command and General Staff College, a US Army major spends her time deeply researching and writing a paper on the organizational impacts created by land-based strategic fires capabilities. She loves to write and has always been passionate about this particular subject. And for the first time in the past few years, she has the time to research and write. In conjunction with her research, she emails the Fires Capabilities Development and Integration Directorate’s organizational inbox, emails contacts in the Fires Center of Excellence, she asks questions at a fires-focused forum, and calls mentors for assistance. In the end, she receives little feedback, even less encouragement, and zero organizational support. Eventually, she abandons the project.

This is a fictional story, but its underlying themes will be familiar to far too many men and women in uniform. A deep interest in a particular subject and the desire to contribute to the intellectual advancement of the profession of arms flounder when met with a lack of institutional support and no defined avenue to be transformed into something useful to the Army. That needs to change.

With the advent of the Army Futures Command (AFC) in 2018, the Army has begun to make monumental strides in its ability to collaborate across industry, think tanks, academia, and Army organizations. We still, however, fall short in fostering collaboration among individuals within the force. Effectively seizing the whole of our intellectual capacity is critical to gaining and maintaining a cognitive edge across the entire DOTMLPF-P spectrum—doctrine, organization, training, materiel, leadership and education, personnel, facilities, and policy. The time has come for the Army to redefine the way it collaborates with individuals across the force. Specifically, the Army needs an institutional solution that:

- enables individuals the freedom to pursue their interests in strategic scholarship external to and within the limits of their current duty assignments—without derailing professional or personal timelines;

- enhances collaboration and facilitates nearly immediate feedback from the force on strategic issues;

- requires only a nominal investment of resources, time, and personnel to manage; and

- reinforces a culture of innovation and learning within the force.

The Problem

Existing programs and methods for collaboration are insufficient. Calls for papers are often ignored and written in vacuums, AFC’s “soldier touch points” are narrow and limited in scope, and senior leader forums and conferences are often unknown to the force as a whole or are not inclusive. Likewise, using organizational inbox emails as a collaboration tool is also ineffective because the inboxes are often unknown to individuals in the force and are sometimes neglected by the organizations that manage them. The Army lacks a robust, formalized system for collaboration that is inclusive of all uniformed personnel—regardless of duty assignment or location.

An Institutional Solution to Cultivate Innovation

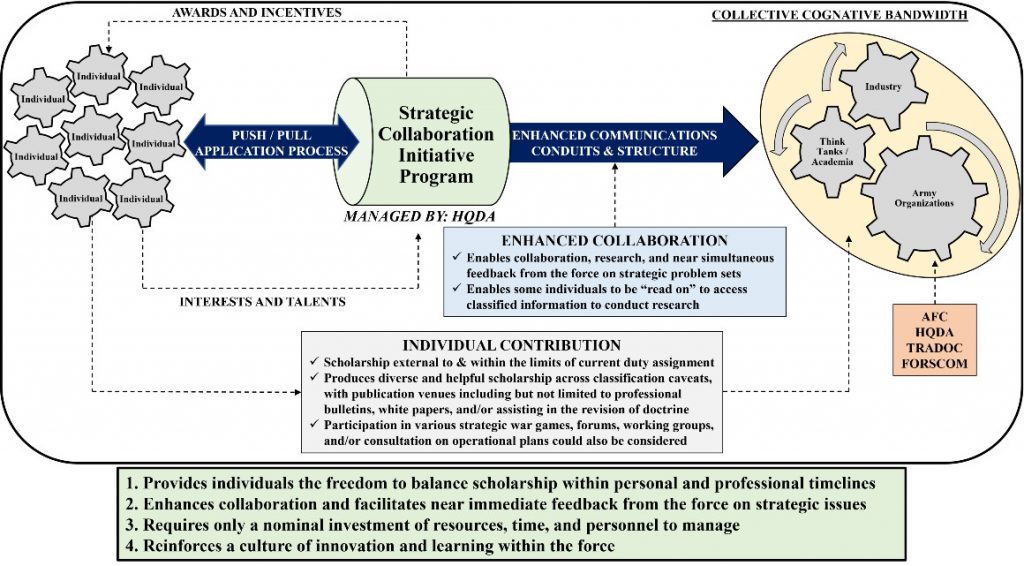

To solve this institutional problem, the Army needs an institutional solution. The one I propose is a new program—a Strategic Collaboration Innovation Program (SCIP)—to provide a structure for effective collaboration between individuals across the force. The SCIP would produce immediate feedback from the force on strategic issues and would reinforce a culture of innovation and learning. The scholarship would span classification caveats and would contribute to professional bulletins, produce white papers, and assist in the revision of doctrine. Outside of published works, participation in various strategic war games, forums, and working groups could be facilitated and consultation on operational plans could be considered. The nature of collaboration would necessarily take different forms: senior members of the SCIP could mentor junior members, members could collaborate as part of a network on long-term projects or when ad hoc opportunities arise, and individuals could work alone on identified institutional priorities. The program would be limited only by the boundaries of its mission: to enable creative solutions to complex problem sets.

Establishing and maintaining the SCIP would require a nominal investment of resources to manage, but would provide vital communications structures to enhance collaboration across vested Army organizations, academia, and industry. Ideally, the SCIP’s size would be relatively small initially—fewer than one thousand servicemembers—with the flexibility to grow as interest and time permit. The program would most effectively be managed by a team within the Headquarters of the Department of the Army (HQDA) to enable effective management of the portfolios of individuals conducting research that spans the breadth and depth of strategic focus areas across Training and Doctrine Command (TRADOC), AFC, Forces Command (FORSCOM), and HQDA. As an additional benefit, the SCIP would help provide continuity across these organizations, many of which have a stake in researching and solving similar or related strategic problem sets.

The SCIP would also provide an effective instrument to help focus the research of its members with a “push-pull” application process to match strategic need with individual talents and interests. With input from TRADOC, FORSCOM, and AFC, the centralized application process would be managed by HQDA—with special emphasis on scholarship that falls within published strategic focus areas. In this process, individuals would be encouraged to apply for areas of scholarship by “pushing” their interests forward, while the Army can focus research areas by “pulling” for scholarship with a list of published strategic initiatives—like the Army’s campaign of learning objectives. Applications should be renewed for consideration annually to maximize talent and productivity within the group.

Collaboration would be enhanced by incentives for excellence in scholarship, as well as minimizing impediments for those within the SCIP. Balancing research, work, and life is difficult. An individual’s ability to research will vary throughout a career as he or she navigates key developmental assignments, training exercises, deployments, and life experiences. Therefore, high-quality scholarship should be rewarded, and contributing members of the SCIP should have their membership annotated on their Soldier Record Briefs and in personnel records. Further, the Army must take care not to disincentivize participation within the SCIP with inflexible timelines. The SCIP must provide its members some flexibility in the timelines for scholarship deliverables to account for fluctuations in professional and personal requirements.

Access to Information: Avoiding a Potential “Firewall” to Collaboration

For some research areas, the program would necessarily require access to classified information, classified networks, and a standardized information security program. While these and other requirements are beyond the scope of this article, the diverse information security needs of local installation tenants coupled with a SCIP participant’s research would require patience and flexibility—with the local installation’s mission requirements always taking priority (e.g., Secret Internet Protocol Router terminals are a finite resource that should be prioritized for mission requirements). The relatively small size and scope of the SCIP, however, would make the process manageable. Further, not every individual within the SCIP would require access to classified information to conduct research, further mitigating the demands on the program.

The SCIP would represent an important evolutionary step in the Army’s People First strategy. The program would leverage our people as the greatest asset in the Army, providing additional cognitive bandwidth and continuity to organizations like TRADOC, FORSCOM, and AFC. It would promote a culture of innovation and learning within the force, allow individuals to pursue their interests in strategic-level scholarship throughout their careers, and enable the Army’s mission by providing individual talent to the force at the time and place it adds the greatest value. Finally, because the program would require few resources to implement and maintain, the potential benefits far outweigh any costs associated with the program. With the ever-evolving threat landscape that the Army must be prepared for, the SCIP would be instrumental in leveraging talent to create a more lethal, future-oriented force.

Major Jeffrey E. Horn, Jr. is a field artillery officer with III Corps Joint Fires Cell. He commanded twice in the 101st Airborne Division Artillery at Fort Campbell, Kentucky, and served his lieutenant time in the 3rd Cavalry Regiment at Fort Hood, Texas. He holds a bachelor of music from Southern Methodist University, a master of arts in security management from American Military University, and a master of operational studies from the Command and General Staff College.

The views expressed are those of the author and do not reflect the official position of the United States Military Academy, Department of the Army, or Department of Defense.

Image credit: Staff Sgt. Chad Menegay, US Army

I am confused by your use of scholarship. It implies a more academic use. E.g. enrollment in a formal accredited institution. These methods already exist and are utilized. You are not addressing the core problem: the concept for collaboration and innovation, which implies time to tackle problems in 'new or different' ways that are not formal institutions. You either want to give more time to use the scholarship: which if you are going the formal route is defined by academic year. Or you want to dictate what problems the individual should solve, which is already incorporated into many of the graduate/doctoral scholarship processes. It sounds like you want to allow all uniformed members time and resources to do non-standard/informal research and solution development while on active duty, which is truly innovative and outside the box. However, requires the cost of taking more out of the fight to do this.

Soldiers are already writing articles and researching topics for college and professional military education courses. Why not leverage this work through a mechanism such as the SCIP? Major Horn's proposal could incentivize the good work already being done by collating and distributing it to interested parties (e.g., AFC, various think tanks, journals, etc.). Moreover, the Army could further formalize the process through SCIP membership to which Horn alludes (i.e., Army SCIP Fellow?). I could envision an annual SCIP Conference where Fellows present papers, conduct panel discussions, and so forth. The only thing I would add to this proposal is that it ought to emphasize inclusion of all ranks–officer and enlisted. There's a lot of intellectual capital to benefit the joint force if we are willing to cast our "nets" wider. Well done, Major Horn!

This is a great, thought-provoking piece proposing an innovative program, worthy of support, but it will take years to realize. We cannot wait that long.

I caution about building any program that relies too heavily on SPIR for information sharing. This will be an insurmountable barrier for most in the ARNG and USAR to meaningfully contribute. Of the 20 Army Reserve Officers assigned to my command, I am the only one with current SIPR access.

In the immediate term, how do we tackle the fictional vignette presented at the beginning of the commentary? I submit that as an institution we need to reconstitute and invest in our professional journals across several media platforms (online and in print). As a "geezer", I can attest that these Army journals were once more robust with lively debate and provided Company and Field grade Officers with a low-barrier-to-entry opportunity to research, write, and reflect in a medium that mattered and influential people actually read.

One by one, our branch journals have been starved of resources, merged with other areas of emphasis, or made "online only", which is a nice way of saying, for all practical purposes, that no one reads them anymore. Numerous online-only, niche publications have stepped into the breech over the past 15 years but few survive and none can capture the institutional vitality or legitimacy that "Infantry", "Armor", and "Fires" once had.

This short-sighted atrophy of the Army's quasi-academic writing platforms extends beyond the branch journals. Military Review abolished the printed publication of its book reviews in 2018, a very short-sighted decision that eliminated one of the easiest ways to give young, intellectually curious Officers an opportunity to write short pieces for publication. Then there is the migration of NCO Journal into its current "online only" format which is a sad husk of what it once was despite the cool pictures. The benefits of virtualizing our publications was oversold because what's the point of beautiful layout if no one reads it and no one engages or comments? The overwhelming majority of Soldiers or Officers simply will not read this virtual content in their off-duty time when they carry the "world" in their phone – it's just reality. If you don't invest in printing a physical option that is accessible in the workplace, most won't read it, or even look at it.

The hour is late if the Army wants to save these publication platforms which are our institutional, intellectual heritage. I still subscribe to Army Sustainment and Special Warfare in print. Army Sustainment is down to four, much thinner issues a year that now encompass five unique (!) branches: AG, FI, OD, QM, TC. In a good year, Special Warfare gets published twice and is riddled with distracting typos.

I remember when "Infantry" was a must-read publication in the 1990s and have several copies that were the basis for solid OPDs when I was a LT. It also educated me during endless nights on staff duty. Many ideas brought to the fore for discussion in those issues came from CPTs and MAJs. Perhaps these reflections are the rantings of an SSC-bound "geezer," but I do think there is merit in at least discussing what we've lost intellectually and what can still be reclaimed for future generations of Army leaders. We can never stop innovating, but sometimes the tools of the past deserve a second life as well.