Editor’s note: This article is the third in a five-part series on educating Army leaders for future war. Read parts one and two.

The year is 2040 and the United States is locked in a high-intensity conflict with a near-peer adversary. An Army division is tasked with controlling a major highway to provide security and support another division’s assault to seize an objective on key terrain. To control this highway, now currently in enemy hands, the division must breach defensive obstacles and clear the enemy off the route. After employing its unmanned aerial and ground reconnaissance systems, launching loitering munitions, conducting electronic warfare attacks, and employing precision fires, an infantry brigade prepares to breach.

Several hundred kilometers away, the division commander walks into the operations center at one of the small, mobile command posts the division is employing. He quickly issues orders to his staff and demands to see the live video feed from the infantry brigade’s drones so he can control the battle at the decisive point—the breach.

This is exactly the kind of situation this commander had prepared for. At Fort Bragg, he routinely trained for scenarios like this, developing a mental playbook so he could quickly react to the enemy’s actions. He is prepared to control the battle through advanced communications platforms and a state-of-the-art battlefield tracking system that utilizes cutting-edge artificial intelligence. He is intently focused on the maneuver of the infantry brigade, the main effort for the division’s mission to control the highway. With a tab on his shoulder and badges on his chest, he possesses the traits and experience that the military has traditionally valued. He is exceptionally fit, is confident in his decisions, maintains his bearing and composure under pressure, and acts decisively. He has even prepared himself by reading military history and theory throughout his career. Once an Eagle, Marie and Carl von Clausewitz’s On War, and the Ranger Handbook adorn his bookshelf. He is the type of officer the Army holds up as the ideal steward of the profession. He is ready.

Suddenly, the video feed cuts out and all radio communications fall silent. The division headquarters can no longer communicate with its subordinate units, and it can no longer take control of its semiautonomous aerial and ground reconnaissance platforms. The division’s leadership is effectively isolated from its brigades, unable to provide them with assets or guidance. The breaching element is on its own.

To make matters worse, just before the battlefield tracking system shuts down from an enemy cyberattack, the division staff is alerted that the command post has been targeted by enemy long-range precision fires and air-delivered precision munitions. To have any hope of survival, the staff must immediately move the command post, launch drones to spoof their positions as they disperse to make them more difficult to target, and employ directed-energy defense systems against the incoming munitions—all of which must be synchronized and happen faster than any one individual could control. The staff must completely trust one another, act without directions, and communicate clearly in order to survive.

What are the traits required for effective leadership in a complex situation like this? And how do those traits differ from those the Army strives to foster in its leaders today? By examining leadership traits in context, using data from the Army’s annual leadership survey to do so, it becomes apparent that while the Army builds very competent leaders for both simple and complicated contexts, the service struggles to build leaders who thrive in the type of complexity that will characterize the future battlefield.

Leadership in Context

The previous article in this series continued an examination of the Cynefin framework as a tool to help describe the changing context of war. This framework helps categorize and make sense of war’s increasing complexity over time, but it is also fundamentally a framework about leadership. For each context they describe—simple, complicated, complex, and chaotic—David J. Snowden and Mary E. Boone discuss the role of leaders in that context, common pitfalls, and how leaders should avoid them. Unlike much of the Army’s context-agnostic leadership training, this framework helps describe the critical relationship between context and followers, two-thirds of leadership’s paradoxical trinity.

Each of the four contexts requires different leadership styles and processes to maximize leaders’ effectiveness. Simple contexts are the domain of best practice in which the leader’s job is to delegate authority and ensure that proper processes are in place. They must first assess the situation (sense), determine the nature of the problem (categorize), and then apply known solutions and best practices (respond). Many day-to-day tasks Army leaders perform, such as managing a training calendar or conducting vehicle maintenance, fit this pattern. Leaders need to guard against complacency and be willing to shift away from previous practices if the environment shifts.

Complicated contexts may have specified solutions, but they typically reside with subject matter experts rather than an organization’s leaders. In complicated contexts, the leader’s job is to receive, manage, and synthesize input from experts. After assessing the situation, leaders must analyze a problem rather than simply categorizing it before they can craft an appropriate response. Determining the best methods to incorporate a new piece of technology or equipment into a unit’s operations may fit this category. Leaders must not be overconfident in either their own solutions or the efficacy of past solutions, as complicated contexts can still present novel and wicked problems.

Chaotic contexts require leaders to act quickly and decisively and then analyze the situation after the crisis has abated. While these situations play to the current strengths of many Army leaders, two points about chaotic contexts are important to keep in mind. First, while combat is often chaotic, war is not an endless series of chaos requiring action without thought. Second, as Snowden and Boone discuss, chaos should engender innovation. Successful leaders should simultaneously manage a crisis while seeking ways to adapt their organization, while unsuccessful ones use crisis as an opportunity to reassert centralized leadership for much longer than is necessary.

Future warfare, as the previous article explored, will increasingly move toward the remaining context Snowden and Boone identified—complex. Complex contexts cannot be solved; they can only be managed. In a context with variables and relationships that are constantly shifting, leaders are unable to assess the situation and apply the appropriate solution. Instead, they must begin by intentionally probing the environment and conducting small, experimental actions to generate insights they can then analyze for patterns. They must have patience to allow patterns to emerge and must be flexible enough for their responses to fit emergent patterns. Snowden and Boone provide specific tools for leaders operating in complexity, including creating an environment that prioritizes two-way discussion rather than one-way communication, promoting diversity, and encouraging dissent. Leaders operating in complexity must therefore establish a culture that fosters trust by encouraging open communication and interaction between the entire team. Operating in complexity therefore requires not only adaptability and patience, but also empathy and transparency.

Leaders unaccustomed to or untrained for complex environments will instinctively try to fall back on top-down leadership models that are best suited for simple or complicated contexts. In an attempt to solve problems, they will often rush to action by swiftly applying the solutions or processes with which they are comfortable. But without taking time to understand the system’s patterns, these actions may have no lasting impact, or might even exacerbate the problem. In the hyperactive battlefields we may see in future wars, leaders should not immediately rely on the tactics, techniques, and procedures most familiar to them. Instead, they will need deliberate plans to stimulate the environment and the enemy’s system, analyze the response, and then adjust their plans accordingly. To do this effectively, the Army needs a new model of leadership education and training to intentionally develop attributes and competencies different from those that were the most important for twentieth-century warfare.

Testing Leader Traits: Unprepared for Complexity

The character of military command evolved to be top-down and managerial because that model best allowed commanders to focus on the principal task of controlling forces in relatively constrained time and space. The character of military leadership matched the character of warfare. This match allowed the Army to develop leaders that fit a mold optimized for managerial leadership. Though small facets of the mold have changed over time, its basic shape has endured to the point that it has become embedded within Army culture. We have erroneously come to believe that leadership traits suited to the previous character of military leadership actually represent the nature of leadership. To develop leaders for complex wars in the future, we need to reprioritize the leadership traits the Army values most. We need to reshape the mold.

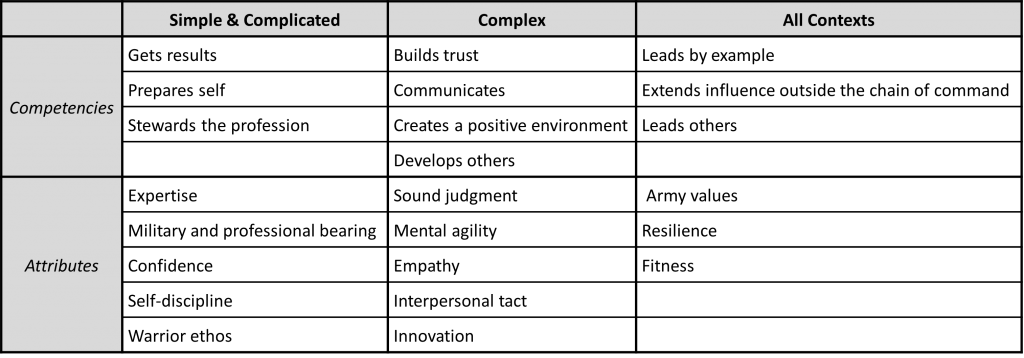

The Army’s leadership doctrine breaks relevant traits into two broad categories: competencies and attributes. Competencies are the behaviors and actions leaders take, while attributes are the internal characteristics of who leaders are. The doctrine treats each of these traits equally, failing to acknowledge that the relative importance of these traits changes in different situations. Examining them through the lens of the contexts outlined in the Cynefin framework is instructive.

Simple and complicated contexts are mechanical in the sense that there are cause-and-effect relationships and problems are solvable. Leaders in these contexts should therefore demonstrate the traits that allow them to manage teams without necessarily needing to build them. Traits focused on individuals and the proper application of resources are best suited for simple and complicated situations. Those traits from the Army’s leadership doctrine that are especially pertinent here include “prepares self,” “gets results,” “military and professional bearing,” “fitness,” “confidence,” “self-discipline,” “warrior ethos,” and “expertise.” The “stewards the profession” competency also fits mechanical systems in which the same best practices should be repeatedly applied to solve problems. On the other hand, complex contexts are dynamic and unsolvable by nature. Leaders operating in complexity need traits that enable them to build strong teams that can react nimbly when situations change. Traits focused on team building, interpersonal skills, and communication are therefore better in complexity because it is teams, not individuals, who generate success. In Army doctrinal terms, these traits include “creates a positive environment,” “communicates,” “builds trust,” “develops others,” “mental agility,” “sound judgment,” “empathy,” “interpersonal tact,” and “innovation.” The former set of traits is important for solving known problems, while the latter set is necessary to determine what the problem is and empower a team to address it.

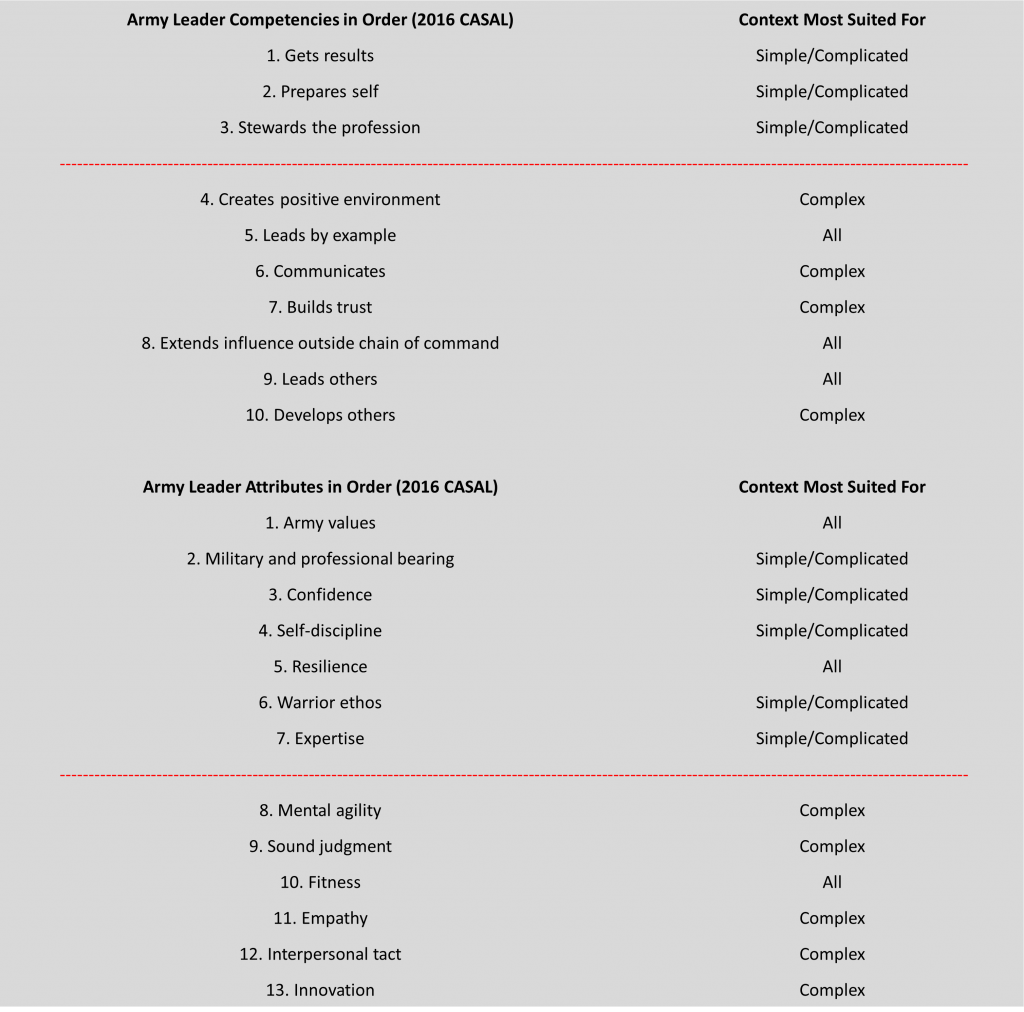

The Center for the Army Profession and Leadership (CAPL) conducts a survey of Army leaders called the CASAL—CAPL’s Annual Survey of Army Leadership. Though the survey results were last made public in 2016, the responses are illuminating. Nearly eight thousand officers and noncommissioned officers answered questions about the effectiveness of their leaders across various categories, the results of which were then grouped by competencies and attributes. The three most demonstrated competencies, in order, were “gets results,” “prepares self,” and “stewards the profession.” The least demonstrated competencies included “develops others,” “leads others,” and “extends influence outside the chain of command.” The most demonstrated attribute was “Army values,” followed by “military and professional bearing,” “confidence,” and “self-discipline.” The least demonstrated leader attributes were “innovation,” “interpersonal tact,” and “empathy.” These results largely mirror one of the first CASAL surveys in 2009, although the relative ranking of “leads others” and “mental agility” both fell out of the top three traits from 2009 to 2016.

The takeaway from this data is clear: the Army does a good job developing individual leaders for simple and complicated situations, like those faced in day-to-day training, but struggles to build leaders for the complexity of twenty-first-century warfare. To be sure, the Army will always need leaders who are focused on winning and getting results. There will be times Army leaders need to simply take charge and act quickly and decisively, especially during periods of chaos. But it is worth asking what “gets results” (the top competency of Army leaders today) should look like in the future. “Results” in today’s Army are primarily associated with quantifiable, managerial tasks, like physical fitness scores, unit readiness, and proficiency on basic soldier skills. In the future, unit readiness and training will be no less important, but basic unit tasks and skills will be different and often less quantifiable. Commanders will need to take their data engineers and AI staff to virtual ranges just like they take their maneuver units to weapons ranges. Soldiers may have to be as proficient at masking electronic signatures and defending networks as they are at calling for fire. Building resilient and cohesive teams that can quickly adapt is certainly a result, but not one that can easily be briefed on a slide during a command and staff meeting. Getting results will still matter, but not in the same way the Army currently thinks about what constitutes a “result.”

It is unlikely that the Army can devise leadership development systems that will create leaders who always excel at everything. While that is the ideal, the reality is that Army leader development must prioritize, deliberately choosing which traits it emphasizes most in its education and training. This choice is fundamentally about where the Army is willing to accept risk in how it selects and trains its most important asset—its people. If we accept the premise that future warfare will be more complex than past warfare, and if the leadership traits the Army currently undervalues are better suited for complexity, there is a logical conclusion: the Army must revamp its approach to leader development.

From Stewards to Entrepreneurs

In a superb article on “the future of strategic leadership,” Steven Metz captured the necessary transition of military leaders by comparing their roles to those of dominant industry leaders. Metz wrote, “In the twentieth century, successful strategic leaders were like the titans of industry, managing increasingly large enterprises and increasingly complex endeavors. Winning often meant bringing the most resources to bear at the appropriate time and place. . . . But future strategic leaders will need to be more like cutting-edge entrepreneurs, out-innovating and out-adapting adversaries.” To achieve this vision, the Army will have to make a deliberate shift in its leadership emphasis from stewards of the profession to professional entrepreneurs.

There are indications that the Army is taking this challenge more seriously, as it has worked to both overhaul its personnel system as well as introduce the concept of mission command. In fact, the traits the Army associates with mission command—”leads others,” “sound judgment,” “communicates,” “innovation,” “empathy,” and “develops others”—are almost the same ones best suited for complexity. Yet writing mission command into doctrine and changing leader development systems and Army culture to embrace mission command are not the same. As other authors have noted, true adoption of the mission command philosophy (originally the Prussian concept of Auftragstaktik) would require a massive culture shift in the Army. The Army’s historical legacy of hierarchical, managerial approaches to command are deeply embedded in organizational culture and cannot simply be undone with new doctrine. Redefining how the Army views leadership as the interaction between context, leaders, and followers may be a better place to start.

Even if the Army takes strides to embrace mission command, there is no indication that doing so, in and of itself, will be sufficient for the challenges of future warfare. The command philosophy may help units operate in a more distributed manner, but mission command alone will not solve commanders’ problems understanding, assessing, and determining patterns in a complex environment in order to properly define their units’ missions. It will not help them discover the best ways to incorporate effects from cyber, space, the electromagnetic spectrum, and the information environment into ground operations. It will not tell commanders how to best protect their units on battlefields where multidomain sensors, loitering munitions, and precision fires make traditional methods of defense nearly obsolete. To solve these problems, the Army must find a way to turn its stewards into entrepreneurs.

Interactive Leaders for a Hyperactive Battlefield

The Army’s list of leadership competencies and attributes is useful for assessing the strengths and weaknesses of leaders in context. As the CASAL survey results demonstrate, Army leaders are far weaker on traits suited for complex environments than they are on those for simple or complicated environments. Yet it is worth asking whether the list of competencies and attributes is even the right list to represent challenges of leadership in future wars. Nonlinear thinking will be critical for commanders to understand the patterns of complex and dynamic battlefields. Future Army leaders will not all have to be engineers, but they will have to have more technological competency than currently exists among the officer and noncommissioned officer corps. If savvy PowerPoint skills are the primary benchmark of technological fluency in ten years, we will be hopelessly lost. Complex environments demand that leaders have patience and humility, as they will not immediately have the right answers and must take time to understand the environment. Deliberate inaction, along with decisive action during windows of opportunity, will also require leaders to be risk tolerant, an attribute that extends beyond the battlefield to create the necessary culture of change and innovation the Army desperately needs. Finally, future leaders must possess better social reasoning skills to understand how various individuals and groups will perceive their actions, and they must deliberately shape the information environment. As the global information ecosystem becomes even more interconnected, narratives will increasingly influence the minds and will of soldiers on the battlefield and the publics whose support for their efforts, in a democracy, is essential.

Though individual leader traits must adapt to the increasing complexity of war, traits focused on developing strong teams will continue to be the most important. Trust, interpersonal tact, empathy, communication, and developing others are essential for success in future warfare. What these traits all have in common, other than that the fact that they are among the least demonstrated by Army leaders today, is that they are fundamentally about leaders’ ability to interact with their subordinates. One reason Army leaders struggle to do this is the significant generational gap between the Army’s senior, mid-career, and junior leaders. Leaders from these three tiers are largely drawn from Generation X, Generation Y (most commonly known as “millennials”), and Generation Z, respectively, and the difference between them is consequential for how individuals build and manage teams. The next article in the series will explain the interaction of leaders and context with the third part of leadership’s paradoxical trinity: followers.

Cole Livieratos is an Army strategist currently assigned to the Directorate of Concepts at Army Futures Command. He holds a PhD in international relations, is a non-resident fellow at the Modern War Institute, and is a term member at the Council on Foreign Relations. Follow him on Twitter @LiveCole1.

The views expressed are those of the author and do not reflect the official position of the United States Military Academy, Army Futures Command, Department of the Army, or Department of Defense.

Image credit: Spc. Ryan Lucas, US Army