In late February 2022, a company-sized Russian airborne column of armored personnel carriers and armored reconnaissance vehicles made its way south on Vokzalnaya street through the Kyiv suburb of Bucha. The forces were part of the Russian airborne brigade that had captured the important airport at Hostomel. The column was intercepted and ambushed by a Ukrainian force equipped with Anglo-Swedish Next-generation Light Anti-tank Weapons (NLAWs). In the ensuing firefight, the bulk of the Russian force was destroyed on the narrow two-lane road. This short, dramatic fight represents the type of combined arms battle in dense urban terrain that has happened throughout Ukraine and promises to continue to be typical of the fighting in the Russo-Ukrainian War. The fighting in Ukraine thus far has verified trends in urban combat demonstrated in other urban battles since World War II and confirms the increasing importance of urban combat in modern war. While much of the reporting from Ukraine is one-sided, and thus prone to bias, there appears to be enough evidence to help illuminate these trends.

Size

Size matters in urban operations. An urban area’s size dictates the means necessary to support any operation to defend or attack it. Two factors play into a city’s size: its population and its physical footprint. More people mean more buildings, streets, and infrastructure to secure or to defend.

Kyiv and Kharkiv, with urban populations of 3.5 and 1.2 million, respectively, are extremely large urban areas. They are similar in population size to the Iraqi cities of Baghdad and Mosul where US and Iraqi forces conducted urban operations. Kyiv’s population is larger than Berlin’s population of 2.8 million during the climactic battle of World War II in 1945. Kharkiv’s population is also comparable Manila’s during its 1945 urban battle, and to Seoul’s during the fighting in that city during the Korean War. Thus, urban combat in Ukraine is occurring in cities with populations that rival the largest urban battles in military history.

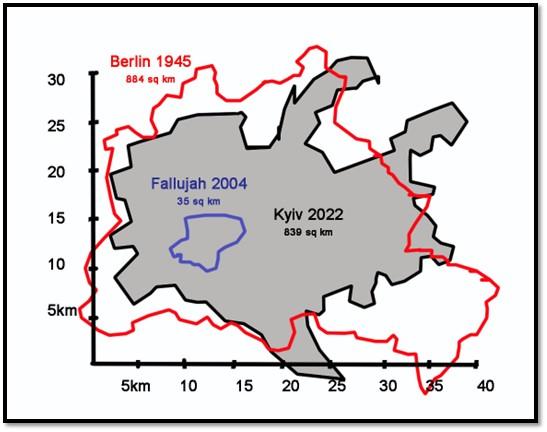

Population is only one measurement of urban size. A city’s physical footprint is the other. Kyiv’s official size is 839 square kilometers while Kharkiv’s urban footprint is about 350 square kilometers. By comparison, Baghdad is 673 square kilometers and Mosul is approximately 180 square kilometers. In 1945, Berlin was approximately 884 square kilometers. In contrast, Seoul in 1950 was only approximately forty-nine square kilometers. Similarly, Fallujah is also very small, only covering thirty-five square kilometers.

Size of the urban area is critical to determining the size of the force necessary to conduct an operation there. The history of urban combat indicates that cities of the physical size and populations of Kyiv and Kharkiv, even accounting for manpower-reducing advances in technology, will require significant force structure to control. Looking at the forces Russia initially committed to the war indicates that there was not nearly enough troop strength to conduct successful urban operations when Ukraine mounted a competent defense.

Force Ratios

A military axiom is that an attacking force should outnumber defenders at the tactical level of war by a ratio of 3:1 to have a reasonable chance for success. Some analysts, including those responsible for US Army doctrine, believe a ratio as high as 6:1 is sometimes necessary to achieve success in urban operations because of the increased strength of the defense on urban terrain. Regardless of the actual requirements, force ratios are relevant for urban planners.

Force ratios at the outset of the war did not favor Russian forces. On the aggregate, the Russian military with an active duty strength of over 900,000 military personnel greatly outnumbered the Ukrainian forces who numbered approximately 196,000. The force ratio, in its most simplistic terms based on manpower, was 5:1. But absolute ratios do not tell the full story. Russian active duty ground forces strength was reported to be approximately 490,000, with Ukrainian army strength at 125,000. These figures reduced the force ratios to approximately 4:1. The total numbers of ground forces engaged on both sides within Ukraine at the beginning of the conflict were roughly 200,000 Russians and about 90,000 Ukrainians. This gave the Russians a force ratio of only slightly better than 2:1. Further enhancing the Russians’ ability to create favorable force ratios is their ability to mass at the time and place of their choosing while the Ukrainians must defend everywhere.

Again, absolute numbers do not tell the full story. Good tactical intelligence helped the Ukrainians anticipate Russian attacks. Furthermore, mobilizing the Ukrainian reserves, in all the various forms that took, changed overall force ratios and brought Ukraine’s ground strength to more than 200,000, a figure not including the mobilized civilian militias and local volunteers. The force ratio between Russian and Ukrainian ground forces upon mobilization approached equilibrium.

Other factors alter the complex calibration of force ratios. The Russians have great superiority in helicopters, surface-to-surface missiles, conventional artillery, tanks, and other armored forces. The artillery and missiles in particular offer Russia considerable standoff capability and do positively offset the force ratios based strictly on manpower. To the Ukrainians’ advantage, defending on urban terrain greatly enhances the combat power of the defender. Additionally, close combat on urban terrain places a premium on motivated, well-trained small units—a strong point of the Ukrainian army. Also complicating the force ratio issues is the fact that the Ukrainian government has issued small arms to civilians, increasing the total defenders in urban areas by as much as tens of thousands. Thus, though the Russian forces in total may have a combat power advantage, overall, they lack the combat power to engage in large-scale combined arms urban operations. This point was validated by their unsuccessful effort to capture the capital of Kyiv. It may prove to still be the case as combat shifts to eastern Ukraine.

Bold Maneuver

The best way to conduct successful offensive operations against an urban center is to capture the urban area before it is defended. This was the key to the successful capture of Seoul through the surprise Inchon landings in 1950. It was also the key to the successful capture of the city of Hue by the North Vietnamese during the Tet Offensive of 1968. Bold strikes are a high-risk endeavor. Russia planned rapid ground attacks synchronized with bold, deep air assaults designed to seize critical urban terrain before it could be defended. The Russians largely failed in northern and eastern Ukraine because of a lack of surprise, insufficient weight in the attacking forces, and competent and aggressive Ukrainian defenses and counterattacks.

Due to the success of the defenders and their own shortcomings, the Russians have been forced to switch to a measured conventional approach—the absolute worst way to attack an urban area. This approach is time consuming, allows the defense to be prepared in depth, and is often costly to the attacker, the defender, the civilian population, and infrastructure. So far, this approach has failed to capture Kyiv, Kharkiv, and Odesa, and resulted in the costly siege of Mariupol.

Isolating the City

If a rapid tempo fails to capture a city from the march before the defense is prepared, isolating the city becomes an essential task for the attacker. This has been Russia’s objective in the operations against Kyiv, Kharkiv, and other major urban centers after the failure of the initial invasion. In 1945, Manila and Berlin were both isolated as part of the successful assaults on the cities. Smaller-scale urban battles such as Aachen in 1944, Hue in 1968, and Fallujah in 2004 also illustrate this operational necessity. Historically, acknowledging the potentially negative effects of being isolated in an urban area, armies have sometimes chosen to withdraw to avoid destruction in the urban area. The North Korean and Chinese armies both abandoned Seoul in 1950 and 1951, respectively, to avoid being trapped and destroyed in the city.

Likewise, keeping a lifeline to the city open is the key to a successful defense. In World War II, the successful defenses of both Stalingrad and Leningrad hinged on the ability of the Soviet Red Army to continue to supply and reinforce those cities’ defenders. In Korea, Pusan was successfully defended in 1950 because of the United Nations forces’ ability to reinforce and resupply through the port and by air.

Once isolated, the defender will lose the city unless a counterattack breaks through to relieve the garrison. In December 1942, the German counterattack to break through to the surrounded 6th Army in Stalingrad failed. Less than two months later, the 6th Army was forced to surrender. Historically, a key to urban operations’ success or failure depends on the isolation of the city and its garrison. In Ukraine, the Russian military did not have the manpower to isolate Kyiv. Attempts to surround Kharkiv have also failed. A key component in the Russians’ strategy to shift focus to eastern Ukraine is to create situations where they have sufficient forces to isolate the cities as they did at Mariupol.

Russian Tactics and Operational Options

Given the obvious Russian operational approach aimed at isolating cities, the Russian military still faces the problem of how to gain control of an isolated urban area. There are three general tactical approaches that the Russians can choose from.

The first is a systematic, combined arms, block-by-block assault to destroy defending forces and establish control of the city. This approach is costly in terms casualties to the attacking force. Likely costs are particularly noteworthy in light of the high casualties the Russian ground forces have suffered in Ukraine. Collateral destruction, in terms of civilian casualties and destroyed infrastructure, would be high as well. Furthermore, a methodical attack plays to the Ukrainians’ strengths of small-unit tactics and morale. Given what has been seen of Russian tactics to date, such an approach would challenge the small-unit training and the morale of Russian infantry and armored forces. It would also require a significant infantry force ratio advantage to overcome the defensive advantages of the urban terrain, even if that terrain is mostly reduced to rubble.

A second operational approach would be to slowly and systematically seize small areas of the urban terrain and then hold them against Ukrainian counterattacks while preparing to take another bite of the city, requiring less combat power than an all-out assault. Precision attacks by artillery and air support, combined with overwhelming force ratios at the point of attack, would ensure the quick success of these individual operations. Still, this requires that Russian forces meet the Ukrainian military where they are strongest: in close combat in urban terrain. Taking bites of the city would be a slower operation but require less manpower. Speed and casualties have become of significantly less concern to Russian commanders as the war has progressed and gone badly. Because this type of approach is slower, it would make the war last longer. The “bite of the apple” approach has not been tried on a large scale in a conventional combat situation recently.

A third approach would be to reduce the city defenses by fire. This plays to the Russian advantages in artillery and airpower. It avoids the close fight until the very end when presumably the Ukrainian forces would be much weakened and Russian casualties could be significantly reduced. In exchange, however, civilian casualties and infrastructure damage would likely be markedly higher than other approaches. Furthermore, relying on fires to reduce the defenses would take more time than either of the more aggressive options..

This is the type of approach used by the Russian army in the capture of the Chechen city of Grozny from late 1999 to early 2000. Sustained heavy artillery and aerial bombardment preceded a slow and systematic assault on the city. Thermobaric weapons and cluster munitions were abundantly used. The city was captured in a three-month battle at the cost of over a thousand Russian soldiers. Grozny was mostly destroyed in the process. Between five thousand and eight thousand civilians were killed in the battle even though most of the city’s population had evacuated. Estimates for the number of civilians left in the city when the fighting started vary from fifteen thousand to fifty thousand. Using the extremes of these numbers, civilian casualties in the battle ranged from 10 to upwards of 50 percent of the population. Similar tactics were used by Russian-supported Syrian troops to capture the city of Aleppo in 2016. This approach, given the current operational situation in Ukraine and the history of Russian urban operations, appears to be the one the Russians chose in the siege of the city of Mariupol.

In modern warfare, all levels of war—tactical, operational, and strategic—meet in the urban environment where vital military, economic, and political infrastructure exist in the same space. Both the Russian and Ukrainian political and military leaders recognize this and thus controlling Ukraine’s urban centers have been the primary objectives of both sides. The war has also verified many of the lessons learned since World War II about the importance of urban warfare and how to successfully conduct it. The future operational details of the war in Ukraine are unknown. What is known is that urban combat will continue to dictate the operational and strategic choices that both sides will make. Also not in doubt is that from the beginning of the war, urban combat has been the key to the tactical, operational, and strategic military and political planning and decision-making. The war between Ukraine and Russia has reaffirmed that urban warfare is central to modern war and will continue to be so.

Dr. Louis DiMarco is a professor in the Department of Military History at the US Army Command and General Staff College. He is a retired US Army armor officer and is a graduate of the US Military Academy and the US Army Command and General Staff College. He earned his PhD from Kansas State University. He is the author of Concrete Hell: Urban Operations from Stalingrad to Iraq.

The views expressed are those of the author and do not reflect the official position of the United States Military Academy, Department of the Army, or Department of Defense.

Image credit: Cpl. Shaylin Quaid, US Army

Wait… Twenty-first century urban warfare ISN'T all about four-man stack teams?!

X(