Warning: Some links in this article lead to websites affiliated with US-designated terrorist groups.

One of the improvised bombs blocks the middle of the screen, but the video is remarkable. An insurgent-operated drone hovers above a Turkish military outpost in northern Iraq before dropping three explosives that damage a motor pool of vehicles. There are also several videos of a fixed-wing drone bombing Turkish foot patrols. On the other side of the conflict, the Turkish counterinsurgents also widely use drones to both observe and strike the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK). In Turkey’s most recent invasion of northern Iraq to fight the PKK insurgency, drones have played a role on both sides.

Recent conflicts, like the Nagorno-Karabakh war, have led to speculation on the revolutionary potential of drones and loitering munitions. The US Army chief of staff recently argued in this forum that drones are the new improvised explosive device, that “everyone’s got lethal unmanned aerial systems now and that’s something we are going to have to really learn to deal with.” Despite their intensive use over the last twenty years of conflict, the impact of drones on irregular warfare is not a settled question.

Do Drones Favor the State or the Insurgent?

Some argue that drone proliferation favors insurgents and terrorists and disadvantages state forces. One report labeled the widespread use of drones by ISIS in Mosul as a “self-made air force” that “achieved their goals at a minimal cost.” There is a belief that “weaponizing is easy” and that this will require the United States (and other counterinsurgents) to change tactics. Besides increasing the tools available to insurgents, drones might be ill suited to counterinsurgency. There is no shortage of articles arguing that drones create backlash against operators.

However, others caution that drones might not be so revolutionary, or at least that their effects are not so favorable to insurgents. There are more significant constraints to militarizing drones than are acknowledged. These constraints also vary by platform. Nonstate groups might easily install forty-millimeter grenades on drones, but struggle to acquire drones or loitering munitions with greater firepower.

Some recent clashes bear this out. Only Yemen’s Houthis—with significant Iranian support—have struck strategic sites like oilfields and airports. Rather, drones act as tactical adjuncts for most nonstate groups. For all of the focus on drones in Nagorno-Karabakh, there were still major urban engagements with mechanized infantry.

On the counterinsurgent side drones have offered many advantages. There is evidence that drones reduce insurgent operations and cause internal fracturing among insurgents. Drones also offer advantages for ground forces compared to other aircraft: when I was a forward observer in Afghanistan, the infantry always appreciated the hours of time on station that drones provided versus the short legs of advanced fighter aircraft. Furthermore, drone strikes might not be as harmful to public opinion as many claim. Rather than creating blowback in Pakistan, for example, only a minority of Pakistanis were even aware of drone strikes.

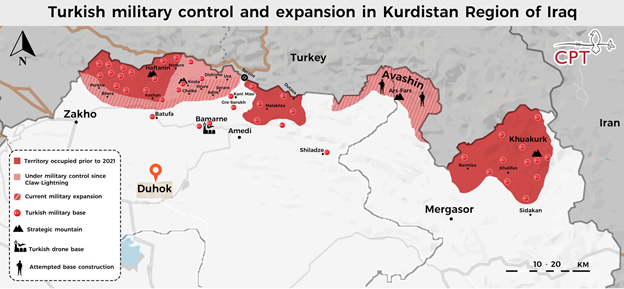

A close look at the ongoing incursion of Turkey into Iraq to target the PKK provides insights into both how drones affected the balance in that conflict and some general lessons for drones in irregular warfare. Turkey launched a new operation against the PKK in northern Iraq in April 2021 (see map below). Turkish drones performed well in Azerbaijan’s reconquest of Nagorno-Karabakh and in Syria. While they might be susceptible to enemies with modern air defense, this is not relevant in the counter-guerrilla conflict where air supremacy is largely uncontested. On the other side, the PKK has begun to use drones in its operations. How have drones affected the military balance?

Drones Help the Insurgent, a Bit

Drones have become an important element of the PKK’s arsenal. The PKK has struck targets with drones for a number of years, although they have sometimes crashed without hitting their target or have been downed by Turkish forces. The PKK uses both quadcopters and larger fixed-wing drones to drop improvised explosives. These drone-dropped explosives appear mostly to be modified mortar shells and forty-millimeter grenades with added fins, apparently from badminton shuttlecocks.

However, the PKK’s drone attacks are neither terribly destructive nor accurate. The rotary-wing drone in the introductory vignette might have damaged a truck or two, but that is no more effective than an improvised explosive device would have been. Drones that drop explosives (instead of crashing into their target) only offer limited gains in accuracy compared to conventional delivery. Furthermore, while early PKK drone attacks were from low altitude, more recent attacks from higher altitude suggest that Turkish success at shooting down drones has required the PKK to be more cautious.

Drones have not replaced traditional insurgent attacks. The PKK also attacks with guide-by-wire missiles, indirect fire, and improvised explosive devices to inflict periodic casualties on Turkey. Drone attacks do make better propaganda videos than traditional attacks because drones have cameras that can record the attacks. However great the propaganda value, the operational value of drones does not appear to be any greater than these other methods of attack. Physics works against the insurgents: small, commercial drones are not the equivalent of large, state-owned drones. Creating a nuisance by inflicting intermittent casualties to the counterinsurgent puts drones on par with other technologies, rather than elevating them to revolutionary status.

Drones Help the Counterinsurgent but Do Not Replace Boots on the Ground

Turkey, like the United States, continues to find success in drone strikes against both low-level soldiers and senior commanders. Although its recent effectiveness is unclear, Turkey claimed in 2017 that drones were responsible for killed by the Turkish military. Turkey has also targeted PKK leadership with drone strikes, even when it risked blowback. For example, Turkey struck PKK leaders who were meeting with Iraqi border guards, at a refugee camp despite US warnings, and as a PKK commander was being medically evacuated from a previous drone strike. Turkey’s airpower has weakened PKK forces and prevented them from massing, just as in other historical cases.

Drones have not erased all of the traditional limitations of manned airpower against insurgencies. The PKK has had decades to prepare positions in the Zap-Metîna and Ava Şîn regions, which has allowed it to develop a series of underground facilities that mitigate Turkey’s prowess in aerial surveillance and targeting. These are difficult to neutralize from the air, requiring Turkey to put boots on the ground to flush out PKK guerrillas. When PKK fighters do emerge from their subterranean lairs, they rely on camouflage such as ghillie suits or white umbrellas in the snow.

Turkey’s drones also have similar vulnerabilities to Turkish military helicopters. The PKK has used man-portable surface-to-air missiles to down helicopters, and claims to have downed at least one drone. Although the PKK’s antiair capability is extremely limited, it has probably required Turkey to use some caution in its use of drones.

Therefore, while drones and airpower have limited the size of PKK infantry operations, the PKK still launches fireteam- and squad-level infantry attacks against Turkish bases and patrols. PKK fighters sometimes overrun listening posts or elements of patrols, and breach the perimeter of bases. Nonetheless, whatever propaganda value these attacks have, the inability of the PKK to mass at the company or battalion level, due to Turkish airpower and drones, limits the group’s ability to inflict serious harm on Turkish forces.

Air dominance has not broken the will of the insurgents. For their part, PKK leaders argue that high morale is their strongest weapon. The PKK’s fighters even record videos of themselves for airing if they are “martyred.” It is hard to not grudgingly admire the tenacity of the guerrillas who live in the mountains without creature comforts, suffer high attrition, and yet continue to fight. That said, the Turks do not lack willpower and continue to employ familiar counterinsurgent tactics alongside new technologies.

Airpower has not changed the requirement for boots on the ground in antiguerrilla warfare. Turkish soldiers wend their way through tunnel complexes used by the PKK. Much the same as Americans in Afghanistan, the Turkish infantry patrols on foot with a minesweeper at the front. Turkey has built a network of roads and combat outposts in northern Iraq, which it is expanding in its current operation. In 2020, Turkey released a map of thirty-seven outposts in Iraq. Turkey is building more bases in this operation to establish a barrier between its border and PKK safe havens. The Turkish minister of national defense visited one such base in May, posting pictures of sandbags overlooking mountains that might remind American soldiers of their time in Afghanistan. Roads connect these bases to one another, with the Turks building at least fifty miles of new roads in the last year. Thus, drones have not created a substitute for infantry in the counterinsurgent fight.

Implications for the United States

If the PKK-Turkey conflict is any indicator, drones aid—but cannot replace—the counterinsurgent infantry who patrol up mountains and down into caves. Turkey’s continued use of ground infantry suggests that a light-footprint approach of relying on airpower cannot provide a military solution to counter an insurgency. Turkey possesses sophisticated air assets yet has realized that boots on the ground are needed to defeat guerrillas. Turkey’s operations are a heavy footprint, with thousands of ground troops deployed, trees cut down, and roads built. It is an effort to kill guerrillas, not win hearts and minds. This is like Israel’s strategy of “mowing the lawn,” an operational solution to overcome the inability of politics to secure Turkey’s Kurdish south.

On the other hand, the proliferation of drones does not create a revolutionary advantage for the insurgent. The PKK is innovative and tries a variety of methods to inflict casualties on Turkey. Yet intermittent mortar rounds dropped from small, commercial drones do not outweigh the disruption that the state’s drones cause to guerrilla operations. Drones will likely continue to be a force multiplier that favors a determined counterinsurgent.

In terms of broader strategy, the United States does not lack opinions on guiding principles: as summarized by Hal Brands and Peter Feaver, there is a spectrum ranging from those advocating restraint, through a light footprint based on the Obama years’ antiterror model and the medium footprint that rolled back the Islamic State, to the advocates of retaining the ability to launch heavy-footprint COIN operations.

The strength of drones suggests medium-footprint strategies of working through determined local proxies might be the best strategy for the United States when facing irregular wars. Determined local proxies can provide boots on the ground, while the long loiter time and precision nature of US drones would be a high force multiplier. “Drones + proxies” might be the new formula for irregular warfare.

Matthew Cancian is a PhD candidate in political science at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. His thesis is about the motivations of combatants and the effects of training, based on a survey of 2,301 Kurdish fighters (Peshmerga) during their war against the Islamic State. Before MIT, he earned a master of arts in law and diplomacy from the Fletcher School and served as a captain in the United States Marine Corps, deploying to Sangin, Afghanistan as a forward observer in 2011 in support of Operation Enduring Freedom.

Matt was a guest on Episode 3 of the Irregular Warfare Podcast along with Dr. Steve Biddle, where they discussed the question “Does Building Partner Military Capacity Work?”

The views expressed are those of the author and do not reflect the official position of the United States Military Academy, Department of the Army, or Department of Defense.

Note on Foreign Language Sources: References to Turkish-language sources are based on Google Translate. References to Kurdish-language sources are based on the author’s own language skills. If you believe the characterization of any source is incorrect, please email the author at mcancian@mit.edu.

Image credit: armyinform.com.us

All true for COIN.

What about State Peer conflicts such as Ukrainian Russian war, or Azeri- Armenian war? The implications there are more profound. In particular since we have fielded no counter-drone capacity to the force.

Following the lessons of those conflicts State to State peer conflict could be far more dicey, Drones loitering over your position dictate displacement or destruction of the ground units if they lack counterdrone capabilities- ground units could be forced into retrograde at a very cheap cost to an enemy indeed.

I would also say look at the Turks- Their Drones have returned Turkey to the table of nations.